Timelines: when can we expect a useful quantum computer?

Reading time: 24 minutes

Contents

- What parameters are relevant?

- How many qubits are needed?

- How long until we have million-qubit machines?

- Putting it all together

- Further reading

The billion-dollar question in our field is:

When will quantum computers outperform conventional computers on relevant problems?

In the previous chapter, we defined the requirements more precisely and coined the term ‘utility’ for such an achievement.

Unfortunately, nobody can confidently answer this question today, and past predictions often proved inaccurate. Moreover, a relevant quantum computer won’t just appear from one day to another: there’s a continuous evolution where these devices will become increasingly capable. In this chapter, we will show how we can make a rough prediction about future timelines and discuss what will happen on the path towards large-scale quantum computation.

As an important disclaimer, this chapter is highly subjective. It’s not hard to arrive at different conclusions simply by choosing other sources and making different assumptions. I did my utmost best to rely on the most up-to-date information, combining the views of the most widely accepted papers and making assumptions that align with the view of most experts to present a balanced perspective.

What parameters are relevant?

Compared to currently available technology, we’d require a fundamental improvement to these specifications:

Number of qubits

Accuracy of elementary operations (gates). This means that quantum computers have the ability to perform long computations without making mistakes.

Quite a few other parameters matter, such as the connectivity, the available set of gates, the speed of operations, and so forth. In this chapter, we choose to simplify matters by assuming that all of these other parameters are not a bottleneck, allowing us to focus only on the number of qubits and gate accuracies.

The relevance of accuracy is often overlooked, perhaps because this hardly plays a role for classical computers anymore. The problem is as follows. A computation consists of many small, discrete steps called quantum gates. Unfortunately, even the most precisely engineered quantum computers are imperfect, and every gate has a slight chance of introducing an error. You can picture this intuitively as a qubit accidentally flipping from ‘0’ to ‘1’ or vice versa1. The probability that a gate introduces such an error on today’s hardware is around 0.1% to 1%. Sometimes the term ‘accuracy’ or ‘fidelity’ is used for the probability of not making an error, translating into numbers like 99.9%.

Now, a serious computation can easily use billions of gates. You can hopefully see the issue here: for long calculations on current hardware, the output is almost certainly garbled by errors. In fact, given a certain error gate fidelity, there is a ballpark maximum number of steps that can be reasonably performed. With a 1:1000 probability of error, we can do roughly a thousand steps, and if the error is one in a million, we can do approximately a million gates. To solve increasingly complex problems, we do not only need to increase the number of qubits, but we also need to reduce the likelihood of errors.

We should take a moment to appreciate the enormous challenge ahead of us. It took decades of engineering to minimise errors to about one in a thousand. Now, we should bring this rate down to one in billions. That’s a huge gap that likely cannot be covered by hardware improvements alone – even a breakthrough that reduces errors by 100x wouldn’t cut it.

Balancing qubits and accuracies

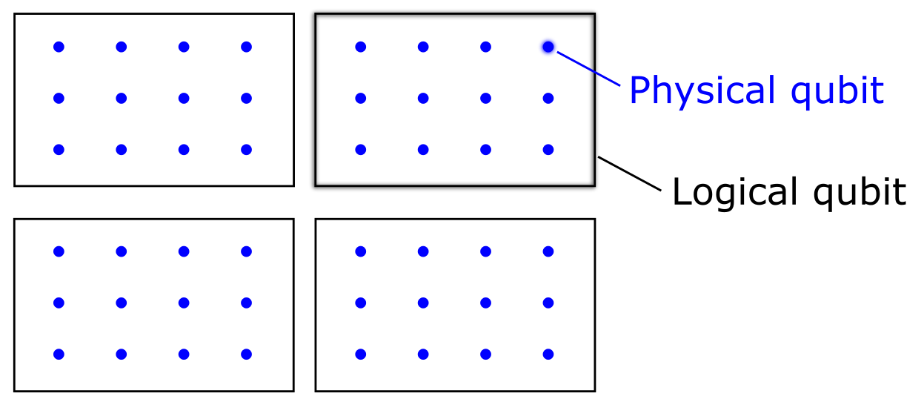

Luckily, there exists a technique that shrinks the probability of mistakes by any desired amount: error correction. It works roughly as follows. For every qubit that an algorithm requires, we don’t just build a single hardware qubit, but instead, we dedicate a large number of qubits, like a hundred or a thousand. We’ll use the term physical qubits for the actual qubits present in the hardware, whereas the virtual error-mitigated ones are named logical qubits.

For example, suppose we have a device with a million physical qubits. In that case, we might group a hundred of these to form a more error-resilient logical qubit, leaving a programmer with just 10.000 logical qubits to use. The image below shows a similar situation with a ratio of 1:12 between logical and physical qubits.

For error correction to work, we need to make several assumptions. For example, depending on the precise error correction protocol, gate fidelities need to be quite good to start with – numbers like 99.99% are often mentioned. This means that, as of 2024, the world’s best devices would still need to improve gate fidelities by more or less a factor of \(10\). Moreover, qubits need to be routinely measured and reset, and large amounts of classical processing are needed to deduce precisely how to repair a given error. These are significant engineering challenges, but experts are optimistic that this can be achieved. We discuss many more details in a separate chapter on error correction.

For now, let’s take for granted that we can somehow reach any desired accuracy (or any desired computation length) by simply adding sufficiently many physical qubits. Then, we can greatly simplify our analysis! For each application, we will forget about errors altogether and only count the number of physical qubits needed.

This leads to an interesting situation. To solve larger, more complex problems, we’ll need more qubits for two reasons: to store more data and to reduce the probability of errors so that the computation can run longer.

Isn’t the focus on just qubits a bit short-sighted? Doesn’t this create a perverse incentive for manufacturers to focus only on qubit numbers, forgetting about all the other parameters? Well, I would indeed be worried that some companies can make headlines with unusable computers that happen to have a record qubit number. Luckily, most manufacturers seem dedicated to making the most ‘useful’ computers, and customers will surely judge their products by the capabilities of their logical qubits. We’re obviously making a coarse simplification here, but making predictions about the future is hard enough as it is.

Back to the main question: When can we expect a large quantum computer? Now that we’re only counting qubits, we can break our billion-dollar question into two parts:

How many qubits are needed?

In what year will that many qubits be available?

How many qubits are needed?

In the previous chapter, we discussed the three main applications of quantum computers: quantum simulation, breaking cryptography, and optimisation.

The most concrete numbers can be given for Shor’s algorithm (breaking cryptography), where we have a very clear problem to tackle: obtain a private (secret) key from a widely-used cryptosystem, like the RSA-2048 protocol. This is the perfect benchmark because there can be no discussion about whether the problem is solved: one either obtains the correct key or one doesn’t. Moreover, we’re quite convinced that even the best classical computers can’t solve the problem (or else you shouldn’t use internet banking or trust software updates).

A recent estimate finds that a plausible quantum computer would require roughly 20 million ‘reasonably good’ physical qubits to factor a 2048-bit number. The whole computation would take about 8 hours2. Such estimates require several assumptions on what a future quantum computer would look like. In this case, the authors assume qubits are built using superconducting circuits, which are laid out in a square grid. Error correction is assumed to be done using the so-called surface code, assuming the best-known methods for error correction in 2020. Note that future breakthroughs could reduce the required time and number of qubits even further.

For chemistry and material simulation, it’s a lot harder to make such estimates because there is not just a single problem to tackle here: one typically uses computers to gradually improve our understanding of a complex structure or chemical reaction. This should be combined with theoretical reasoning and practical experiments. Moreover, classical computers can often perform the same computations that the quantum computer would make at the cost of making certain assumptions or simplifications. There’s a fuzzy region between ‘classically tractable’ and ‘quantum advantage’.

The most concrete task in quantum simulation is to compute the energy of certain molecular configurations. The benchmark is to obtain energies more accurately than done in conventional experiments; one canonically takes the ‘chemical accuracy’ of roughly 1 kcal/mol as the precision to beat. Then, we should focus on molecules where classical computers cannot already achieve such accuracies.

Note that the accuracy of a chemical energy should not be confused with the accuracy of a quantum gate, which is a whole different number.

A highly promising and well-studied benchmark problem is the simulation of the so-called FeMo cofactor of the nitrogenase enzyme, in short, FeMoco. This active site is relevant when bacteria produce Ammonia (NH3), a compound that is of great relevance to a plant’s root system. A better understanding of this process could help us reduce the ridiculously large carbon emissions now associated with the production of artificial fertiliser. We give more details in a separate chapter.

Simulating FeMoco is believed to require around 4 million qubits3 (and around 4 days of computation time). The hardware and error correction assumptions are similar to those of Shor’s algorithm: the estimate is based on a square grid of superconducting qubits, using surface code to correct errors.

For a different enzyme, namely cytochrome P450, it has been estimated that around 5 million qubits are needed4 (again taking roughly 4 days of computation). Altogether, we conclude that a few million qubits (of sufficiently high quality) can make quantum computers relevant for R&D in chemistry.

Some tasks that are mainly of interest for scientific purposes, such as simulating models of quantum magnets, can be achieved with fewer resources. Under similar assumptions, simulating a 2D transverse field Ising model is estimated to take just under 1 million qubits5.

For many optimisation problems, it’s practically impossible to give reasonable estimates. As we saw previously, a true killer algorithm for optimisation problems is not known yet. The algorithms that are presented as the most promising are often heuristic, meaning that it’s hard to predict how accurate their results will be compared to conventional methods. We’ll need to test them in rigorous benchmarks once larger quantum computers become available.

Our perspective starkly contrasts some other sources claiming that quantum computers are already solving practical problems today. But don’t be fooled: these articles state that quantum computers can indeed solve relatively simple problems but often fail to mention that there exist different approaches by which classical computers can solve the same problems much, much faster.

Moreover, many of these algorithms involve optimisation problems that have a plethora of potential solutions, but the goal is to find the optimal solution (say, the one that incurs the least costs or gets you to your destination the fastest). The solution space is often so large that we don’t even know if we hit this optimal solution, but we’re okay with finding one that’s pretty close. Several papers claim that a quantum computer already finds solutions faster, but in all cases, worrying sacrifices were made in the optimality of the solutions for more complex problems.

What about D-Wave’s quantum annealer?

A particularly difficult case is the approach taken by D-Wave. This Canadian scale-up manufactures a quantum computer that is purpose-built to execute a specific optimisation algorithm called quantum annealing. With around 5000 qubits, it can handle reasonably large problems. The bare hardware alone doesn’t seem to perform that well, but D-Wave cleverly combines it with classical high-performance computing in what they call a ‘hybrid’ solver. Comparisons and benchmarks of the hybrid solution report results ranging from ‘much worse’ to ‘very competitive’ relative to classical optimisation solutions. Because it is unclear to what extent the hybrid solver actually exploits quantum phenomena and little is known about D-Wave’s future plans, I don’t dare to make any future predictions about annealing.

See also:

D-Wave claims a scaling advantage when simulating quantum materials.

ETH Zurich researchers conclude that the 2015 version of D-Wave’s annealer is comparable to a modern high-performance CPU.

Los Alamos researchers find annealing speedups in certain cases, but also note challenges to commercial adoption.

Researchers report that D-Wave’s bare quantum hardware is quite slow, but the hybrid solution is very competitive with classical optimisation techniques.

We can summarise our conclusions in the table below.

| Application | How well can we estimate qubit requirements? | Use case example | Physical qubits needed | Gate error assumed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breaking cryptography | Good | Cracking RSA-2048 | ~ 20 million | ~ 0.1% |

| Chemistry | Reasonable | Simulation of FeMoco | ~ 4 million | ~ 0.1% |

| Simulation of P450 | ~ 5 million | ~ 0.1 % | ||

| Optimisation / AI | Bad | ? | ? |

What about future improvements?

It seems almost inevitable that the above methodologies will improve. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to estimate by how much. Will we reduce the number of qubits required by a few per cent? Or by a factor of ten? By a factor of one thousand?

Some sources actually try to extrapolate the reduction in required qubits over time (like Youtube science educator Veritasium6 and a report by McKinsey7), but this is such a wonky extrapolation over a handful of data points that we will not follow this strategy.

On the other hand, it would also be naive to stick to the numbers above without assuming some margin for improvements. In error correction techniques alone, there appears to be steady progress to improve the ratio between logical and physical qubits. Based on discussions with scientists, lowering the qubit requirements by a factor of 3 to 10 seems plausible. Hence, for optimistic readers, we can set another target at around 400.000 qubits. Interestingly, this number is similar to the qubit requirements for the simulation of models that are especially of scientific interest.

| Application | How well can we estimate qubit requirements? | Use case example | Qubits needed? | Gate error assumed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry (Optimistic) | Reasonable | Simulation of FeMoco (with 10x improved methods) | ~ 400.000 | ~ 0.1 % |

| Science | Reasonable | 2D Transverse field Ising model | ~ 900.000 | ~ 0.1 % |

Can noisy algorithms be good enough?

Current quantum computers have a limited number of qubits and are not yet capable of large-scale error correction; they are Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. An important question is: can we already achieve any utility with such noisy devices before the era of large-scale error correction? That is one of the most disputed topics in our field, and therefore it deserves some attention.

A growing community of scientists, startups and enterprises are searching for such near-term applications. If successful, this would massively increase the overall usefulness of quantum computers. Some experts seem optimistic that this is possible, but a larger and more authoritative group remains highly sceptical about NISQ’s utility.

In the past decades, when NISQ devices with just a handful of qubits were just on the horizon, several consultants made ridiculous claims about how such tiny machines would bring an exponential advantage over enormous supercomputers. Now that the field is coming of age, many are becoming more careful. To illustrate, when looking back at a 2021 report, consultancy firm BCG chivalrously admits8:

‘Our assumptions for near-term value creation in the NISQ era, however, have proved optimistic and must be revised.’

The most serious recent claim about NISQ utility comes from the IBM team in a paper titled ‘Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault-tolerance’9, in which a quantum simulation of a specific physical system was performed using 127 noisy qubits. However, their arguments were quickly refuted by further studies that simulated IBM’s impressive quantum experiment on a conventional laptop10.

Maryland-based professor Sankar Das Darma expresses the view of many academics in his opinion article ‘Quantum computing has a hype problem’11. He stresses about NISQ that ‘the commercialisation potential is far from clear’, pointing out that claims of speedups in finance, machine learning and drug discovery have so far come with highly unsatisfying evidence.

That certainly doesn’t mean that NISQ utility is ruled out. Most experts seem to keep an eye on the developments of NISQ applications but will agree that no utility for NISQ machines has been found yet. To illustrate, an overview article about pharmaceutical applications12 has a careful yet suggestive message:

‘Most NISQ algorithms […] rely heavily on classical optimisation heuristics, and the actual run time is difficult to estimate. Furthermore, recent results suggest that in NISQ approaches, the number of measurements required to achieve a given error scales exponentially with the depth of the circuit. For these reasons, here we focus our discussion exclusively on fault-tolerant quantum computers.’

Similarly, a recent overview13 of quantum chemistry seems to remain agnostic with regard to NISQ advantage while pointing out that fault-tolerance has a higher chance of succeeding.

‘… it is difficult to predict when or if algorithms on near-term noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices will outperform classical computers for useful tasks. But it is likely that, at some point, the achievement of large-scale quantum error correction will enable the deployment of a host of so-called error-corrected quantum algorithms.’

In this book, I choose to follow the view of most scientists and stick to the well-understood use cases for early fault-tolerant quantum computers that we discussed previously. Nobody can rule out new breakthroughs that allow NISQ utility, but it seems unwise to count on these. A potential scientific leap could completely stir up our fragile prediction – but so would unexpected backlashes in hardware development or even unforeseen funding stops.

How long until we have million-qubit machines?

Now that we’ve set our target to roughly a million qubits, we’d like to estimate when such hardware will be available. We highlight the following sources:

Road maps and claims of hardware manufacturers

Surveys to experts

Extrapolation of Moore’s law

What do manufacturers say?

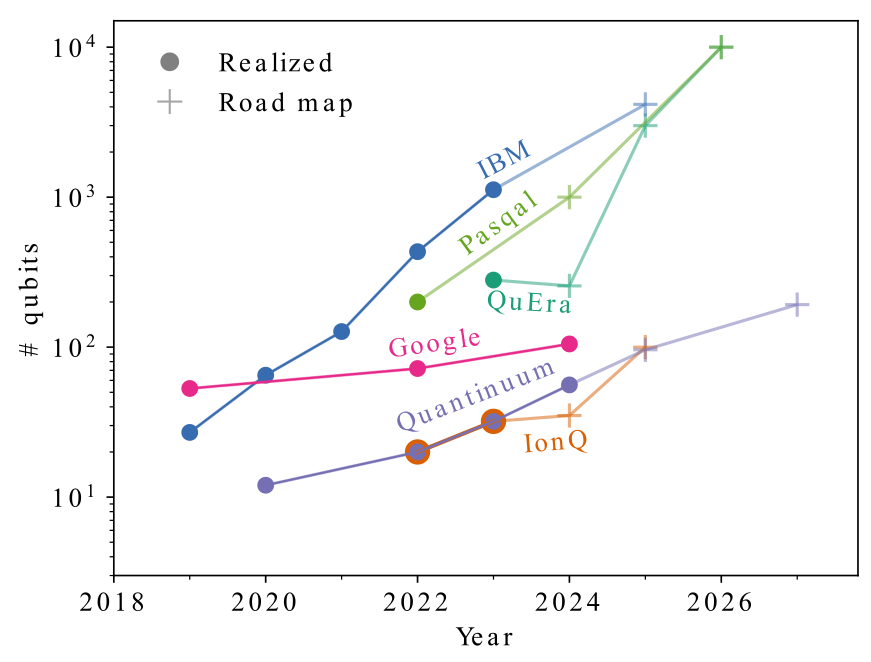

Below, we see the qubit numbers that several manufacturers have already realised (solid disks) and what they will produce in the future according to their public road maps (opaque plusses). Note that the vertical axis is logarithmic, displaying a very broad range from around 10 to 10.000 qubits. A lower number of qubits does by no means indicate that these computers are worse. In fact, the machines with the lower numbers of qubits on this graph have an important edge in other parameters, such as gate accuracies and qubit connectivity.

Figure: The number of qubits in the most mature quantum computers from a selection of various manufacturers, as of 2024.

Besides their road maps, companies sometimes make more daring claims in media interviews or at presentations at large events. Based on the application targets above, it should be no surprise that manufacturers aim for around a million qubits as a ‘moonshot’ accomplishment. Back in 2020, IBM claimed to reach the 1 million qubit target by 203014. Around the same time, Google was interpreted by journalists to do this even faster (around 202915). The start-up PsiQuantum, which made waves thanks to record-high investments of over a billion dollars for their photonic quantum chips, went as far as claiming to have a million qubits by 202516 17.

It seems that these claims were a bit too ambitious. In 2024, with only a year to go and no publicly presented product progression, PsiQuantum shifted its 1 million qubit road map to 202718. IBM took an even more conservative step, where it’s now claiming to have just 100.000 qubits in 203319 (although this machine should meet the error correction assumptions that we dreamingly assumed in the previous sections). Although this delay sounds disappointing, hardware manufacturers are still making impressive progress, as the number of available qubits grows faster than one would predict according to Moore’s Law for classical chips!

Trapped-ion machines tend to have fewer qubits but higher gate accuracies. Perhaps this is why IonQ displays its road map in a different format: they aim to achieve 1024 so-called algorithmic qubits by 202820. This means that IonQ will have at least this number of qubits, but also guarantees sufficient gate accuracy to run reasonably long circuits. It’s unclear whether error correction will be used for this. Competitor Quantinuum recently announced a more concrete road map21, predicting around 100 logical qubits in 2027. These should bring the effective gate errors down by roughly a factor of 10. Looking ahead to 2029, Quantinuum projects 1000’s of physical qubits that form 100’s of logical qubits. This might not be enough to run the algorithms discussed earlier, but it’s not too far off either.

What does Moore’s law say?

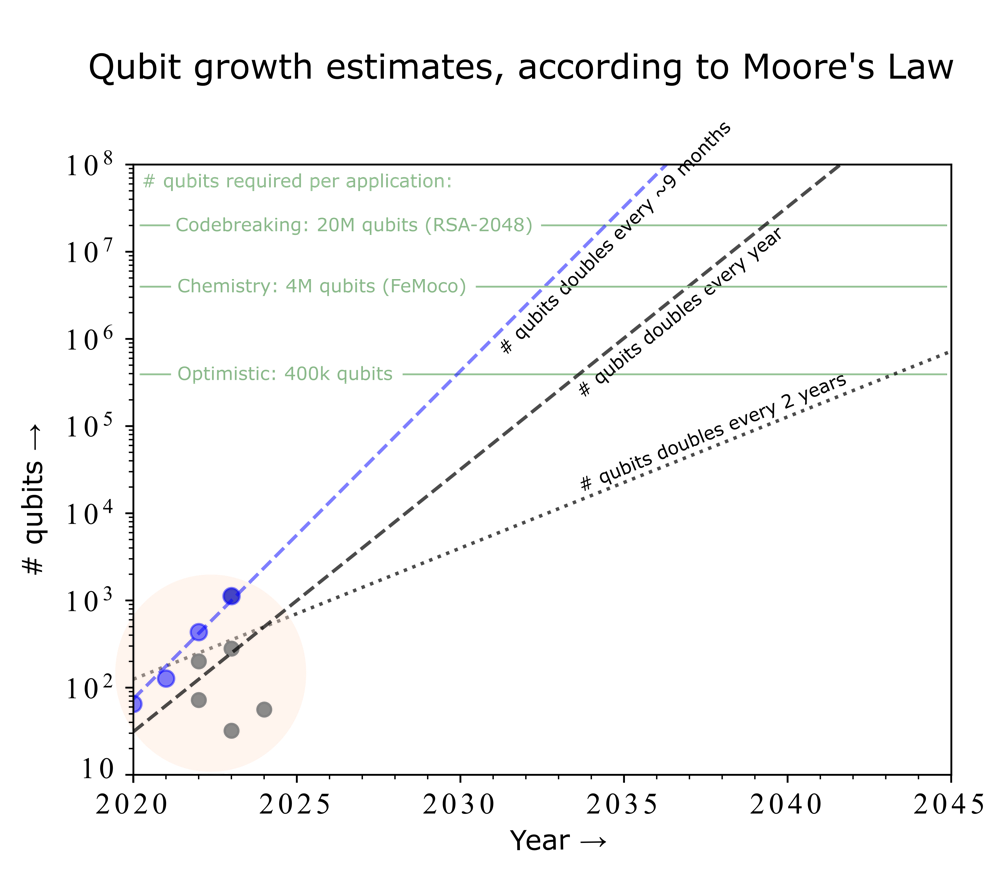

One could assume that quantum computers will ‘grow’ at a similar rate as classical computers. Moore’s law states that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit grows exponentially: the number doubles roughly every two years. This has been a surprisingly accurate predictor for the development of classical IT. If we apply Moore’s law to quantum, then boosting qubit numbers from around a thousand to one million would take around 20 years – predicting that the one million qubit mark won’t be passed until 2044. Clearly, most hardware manufacturers are more optimistic. If we assume the number of qubits doubles each year, one would predict that one million qubits will be available in ten years. While doubling a quantum computer’s size each year is already a daunting challenge, companies like IBM, Pasqal and QuEra set the bar even higher for themselves, hoping to double every 7-9 months.

What do experts say?

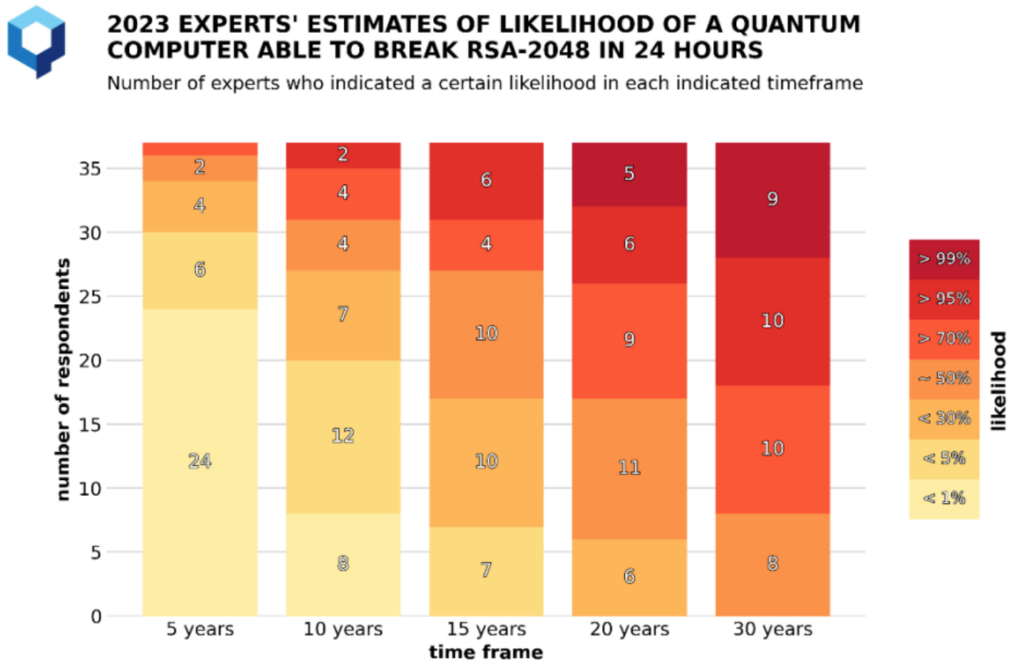

The Global Risk Institute conducts yearly surveys asking experts to state the likelihood that quantum computers will pose a significant threat to public key cryptography 5 years from now. Similarly, respondents would also estimate the likeliness 10, 15, 20, and 30 years away.

This essentially boils down to the question: when will a quantum computer run Shor’s algorithm to crack RSA-2048? We previously saw that around 20 million qubits would be needed for this (although experts may take into account that this number can still be lowered).

We consider this an important source because many important authorities in the field (like professors and corporate leaders) take part in this study. The results from December 202322, gathered from 37 participants, are displayed below.

Figure: Results of the 2023 expert survey by Global Risk Institute (source: globalriskinstitute.org). Image rights belong to Global Risk Institute.

How to read this graph?

Let’s look at the column labelled ‘5 years’. A total of 24 correspondents indicate that there is less than 1% probability that quantum computers pose a security threat in the next five years. A single person is quite pessimistic and assigns a >70% chance that this will happen. On average, experts say that there’s a fairly small likelihood that quantum computers will pose a threat to cryptography in the next five years.

Further to the right, the ratios shift. Looking at 20 years from now, the majority of experts believe that quantum computers pose a serious threat, with over half of them assigning a likelihood of 70% or more.

It appears that the majority of experts believe that the tipping point is between 10-20 years from now. Somewhere between 15 and 20 years away, there’s a point where the median participant assigned roughly 50% chance to see a quantum computer capable of breaking cryptographic codes. However, we should take into account a significant uncertainty: even experts make wildly varying estimates, so there’s no obvious conclusion from this data.

These experts are likely aware of hardware manufacturer’s road maps, as we shall see below.

Putting it all together

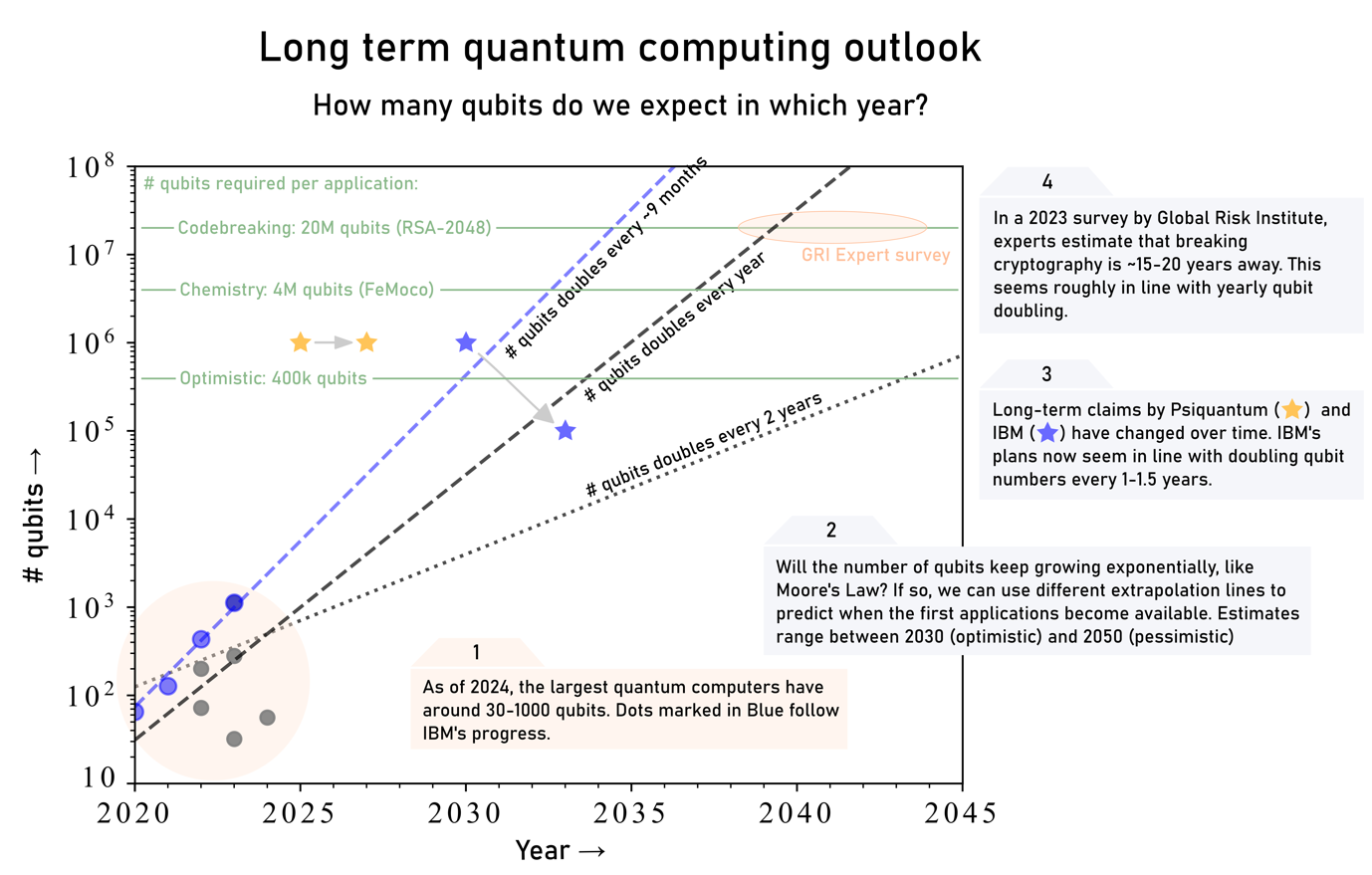

The infographic below sums up our earlier findings.

Assuming that qubit numbers will grow exponentially (and that all other parameters will keep up accordingly), we can consider several scenarios. A pessimistic scenario would be that the number of qubits ‘merely’ follows the classical version of Moore’s Law, and qubit numbers double only once every two years (dotted line). Then, we’d have to wait well past 2040 to reach 100.000 qubits. An even worse scenario would be if we cannot achieve exponential growth, which would stretch the timelines even further.

An extremely optimistic outlook would follow the blue dashed line (which extrapolates the progress by IBM, doubling their qubits every ~9 months). If one also believes in practical applications with much less than a million qubits, then these could be available by 2030.

An intermediate perspective is to assume that the number of qubits doubles annually. Interestingly, this seems to approximately align IBM’s latest claims and the typical expert opinion. Depending on the application, it would mean that quantum chemistry simulation and codebreaking can be within reach between ~2033 and 2040.

To conclude, our estimates strongly depend on the assumptions that you’re willing to accept (who would’ve thought!). Do you believe that improving algorithms and error correction techniques will allow for applications with much less than a million qubits? How quickly do you believe that the hardware will improve? If you force me to make a prediction, I’d say the first applications arise around 2035, with the understanding that there’s a considerable margin for error.

As a final remark, a full utility-scale quantum computer requires much more than just some number of qubits. To reach the first useful applications, we likely require simultaneous progress in algorithmics, software, gate accuracies, error correction techniques, fridges, lasers, and many other important subfields of quantum computing. Hopefully, all these disciplines will find the required breakthroughs that will sustain the exponential growth of quantum computing hardware.

Further reading

- Scientist Samuel Jaques (Waterloo) makes insightful graphs that combine the number of qubits and the error rates, and puts them in the perspective of applications requirements.

Technically, quantum gates are continuous operations, so numbers like fidelity are defined slightly differently. Still, the picture of discrete bit flips is not too much off and will lead to the same conclusions, so I prefer this more accessible explanation. ↩

Gidney, Craig, and Martin Ekerå. ‘How to Factor 2048 Bit RSA Integers in 8 Hours Using 20 Million Noisy Qubits.’ Quantum 5 (April 15, 2021): 433. https://doi.org/10.22331/q-2021-04-15-433. ↩

Lee, Joonho, Dominic W. Berry, Craig Gidney, William J. Huggins, Jarrod R. McClean, Nathan Wiebe, and Ryan Babbush. ‘Even More Efficient Quantum Computations of Chemistry Through Tensor Hypercontraction’. PRX Quantum 2, no. 3 (8 July 2021): 030305. https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.030305. ↩

Goings, Joshua J., Alec White, Joonho Lee, Christofer S. Tautermann, Matthias Degroote, Craig Gidney, Toru Shiozaki, Ryan Babbush, and Nicholas C. Rubin. ‘Reliably Assessing the Electronic Structure of Cytochrome P450 on Today’s Classical Computers and Tomorrow’s Quantum Computers’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, no. 38 (20 September 2022): e2203533119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2203533119. ↩

Beverland, M.E. et al. (2022) ‘Assessing requirements to scale to practical quantum advantage’. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.07629. ↩

See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UrdExQW0cs&t=1024s, starting at 17:04. ↩

McKinsey Digital. ‘Quantum Technology Monitor,’ April 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/steady-progress-in-approaching-the-quantum-advantage. ↩

BCG Global. ‘The Long-Term Forecast for Quantum Computing Still Looks Bright,’ July 3, 2024. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/long-term-forecast-for-quantum-computing-still-looks-bright. ↩

Kim, Youngseok, Andrew Eddins, Sajant Anand, Ken Xuan Wei, Ewout van den Berg, Sami Rosenblatt, Hasan Nayfeh, et al. ‘Evidence for the Utility of Quantum Computing before Fault Tolerance.’ Nature 618, no. 7965 (June 2023): 500–505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06096-3. ↩

Begušić, Tomislav, and Garnet Kin-Lic Chan. ‘Fast Classical Simulation of Evidence for the Utility of Quantum Computing before Fault Tolerance.’ arXiv, June 28, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.16372. ↩

Das Sarma, Sankar. ‘Quantum Computing Has a Hype Problem.’ MIT Technology Review (blog). Accessed September 26, 2024. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/03/28/1048355/quantum-computing-has-a-hype-problem/. ↩

Santagati, Raffaele, Alan Aspuru-Guzik, Ryan Babbush, Matthias Degroote, Leticia González, Elica Kyoseva, Nikolaj Moll, et al. ‘Drug Design on Quantum Computers.’ Nature Physics 20, no. 4 (April 2024): 549–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02411-5. ↩

Cao, Yudong, Jonathan Romero, Jonathan P. Olson, Matthias Degroote, Peter D. Johnson, Mária Kieferová, Ian D. Kivlichan, et al. ‘Quantum Chemistry in the Age of Quantum Computing.’ Chemical Reviews 119, no. 19 (October 9, 2019): 10856–915. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00803. ↩

Hackett, Robert. ‘IBM Plans a Huge Leap in Superfast Quantum Computing by 2023.’ Fortune. Accessed September 26, 2024. https://fortune.com/2020/09/15/ibm-quantum-computer-1-million-qubits-by-2030/. ↩

Finke, Doug. ‘Google Goal: Build an Error Corrected Computer with 1 Million Physical Qubits by the End of the Decade.’ Quantum Computing Report (blog), September 5, 2020. https://quantumcomputingreport.com/google-goal-error-corrected-computer-with-1-million-physical-qubits-by-the-end-of-the-decade/. ↩

Wang, Brian. ‘PsiQuantum Targets Million Silicon Photonic Qubits by 2025’, April 23, 2020. https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2020/04/psiquantum-targets-million-silicon-photonic-qubits-by-2025.html. ↩

ICV TAnK-icv. ‘What Will Million-Qubit Computers Look like in a Few Years?’, 21 March 2022. https://www.icvtank.com/newsinfo/629365.html. ↩

Finke, Doug. ‘PsiQuantum Receives \(940 Million AUD (\)620M USD) to Install a 1 Million Qubit Machine in Australia by 2027.’ Quantum Computing Report (blog), April 30, 2024. https://quantumcomputingreport.com/psiquantum-receives-940-million-aud-620m-usd-to-install-a-1-million-qubit-machine-in-australia-by-2027/. ↩

Baker, Berenice. ‘IBM Details Road to 100,000 Qubits by 2033.’ IoT World Today. Accessed September 26, 2024. https://www.iotworldtoday.com/industry/ibm-details-road-to-100-000-qubits-by-2033. ↩

Chapman, Peter. ‘Scaling IonQ’s Quantum Computers: The Roadmap.’ IonQ (blog), December 9, 2020. https://ionq.com/posts/december-09-2020-scaling-quantum-computer-roadmap. ↩

Quantinuum. ‘Quantinuum Accelerates the Path to Universal Fully Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing,’ September 10, 2024. https://www.quantinuum.com/blog/quantinuum-accelerates-the-path-to-universal-fault-tolerant-quantum-computing-supports-microsofts-ai-and-quantum-powered-compute-platform-and-the-path-to-a-quantum-supercomputer. ↩

Mosca, Michele, and Marco Piani. ‘Quantum Threat Timeline Report 2023,’ 2023. https://globalriskinstitute.org/publication/2023-quantum-threat-timeline-report/. ↩