The applications: what problems will we solve with quantum computers?

Reading time: 27 minutes

Contents

- What applications offer a quantum speedup?

- How can we compare different types of speedups?

- Where is the killer application?

- Further reading

In the previous chapter, we saw that quantum computers have relatively low clock speeds, but they happen to solve some problems more efficiently, that is, in fewer steps. Therefore, the most important question in this field is: what advantage do quantum computers have on which problems?

The Quantum Algorithm Zoo1 lists pretty much all known quantum algorithms. It has grown into an impressive list that cites over 400 papers. Unfortunately, upon closer inspection, it’s hard to extract precisely the useful business applications, for a few reasons. Some algorithms solve highly artificial problems for which no real business use cases are known. Others may make unrealistic assumptions or may only offer a speedup when a problem grows to outrageously large problems (that we never encounter in the real world). Nevertheless, it’s definitely recommended to scroll through.

For this book, we take a different approach. We focus specifically on algorithms with plausible business applications. To assess their advantage, we split our main question into two parts:

What applications offer a quantum speedup?

How large is this speedup in practice?

What applications offer a quantum speedup?

We foresee four major families of use cases where quantum computing can make a real impact on society. We briefly discuss each of them here and link to a later chapter that discusses each application in more depth.

1. Simulation of other quantum systems: molecules, materials, and chemical processes

Most materials can be accurately simulated on classical computers. However, in some specific situations, the locations of atoms and electrons become notoriously hard to describe, sometimes requiring quantum mechanics to make useful predictions. Such problems are the prototypical examples of where a quantum computer can offer a great advantage. Realistic applications could be in designing new chemical processes (leading to cheaper and more energy-efficient factories), estimating the effects of new medicine, or working towards materials with desirable properties (like superconductors or semiconductors). Of course, scientists will also be excited to simulate the physics that occur in exotic circumstances, like at the Large Hadron Collider or in black holes.

Simulation is, however, not a silver bullet, and quantum computers will not be spitting out recipes for new pharmaceuticals by themselves. Breakthroughs in chemistry and material science will still require a mix of theory, lab testing, computation, and, most of all, the hard work of smart scientists and engineers. From this perspective, quantum computers have the potential to become a valued new tool for R&D departments.

Read more: What are the main applications in chemistry and material science?

See also:

Startup PhaseCraft studies the famous Fermi-Hubbard model using a quantum computer

Startup Zapata reduces the runtime and error rate of famous chemistry algorithm

An overview of various simulation software packages for quantum computers

2. Cracking a certain type of cryptography

The security of today’s internet communication relies heavily on a cryptographic protocol invented by Rivest, Shamir and Adleman (RSA) in the late 70s. The protocol helps distribute secret encryption keys (so that nobody else can read messages in transit) and guarantees the origin of files and webpages (so that you know that the latest Windows update actually came from Microsoft, and not from some evil cybercriminal). RSA works thanks to an ingenious mathematical trick: honest users can set up their encryption using relatively few computational steps, whereas ‘spying’ on others would require one to solve an extremely hard problem. For the RSA cryptosystem, that problem is prime factorisation, where the goal is to decompose a very large number (for illustration purposes, let’s think of 15) into its prime factors (here: 3 and 5). As far as we know, for sufficiently large numbers, this task takes such an incredibly long time that nobody would ever succeed in breaking a relevant code – at least on a classical computer. This all changed in 1994 when computer scientist Peter Shor discovered that quantum computers happen to be quite good at factoring.

The quantum algorithm by Shor can crack RSA (and also its cousin called elliptic curve cryptography, abbreviated ECC) in a relatively efficient way using a quantum computer. To be more concrete, according to a recent paper, a plausible quantum computer could factor the required 2048-bit number in roughly 8 hours (and using approximately 20 million imperfect qubits). Note that future breakthroughs will likely further reduce the stated time and qubit requirements.

Luckily, not all cryptography is broken as easily by a quantum computer. RSA and ECC fall in the category of public key cryptography, which delivers a certain range of functionalities. A different class of protocols is symmetric key cryptography, which is reasonably safe against quantum computers but doesn’t provide the same rich functionality as public key crypto. The most sensible approach is replacing RSA and ECC with so-called post-quantum cryptography (PQC): public key cryptosystems resilient to attackers with a large-scale quantum computer. Interestingly, PQC does not require honest users (that’s you) to have a quantum computer: it will work perfectly fine on today’s PCs, laptops and servers.

Read more: How will quantum computers impact cybersecurity?

See also:

(Youtube, technical) MinutePhysics explains Shor’s algorithm.

Nature feature article: The race to save the Internet from quantum hackers

At the time of writing, a complex migration lies ahead of pretty much every large organisation in the world, which comes in addition to many existing cybersecurity threats. The foundations have been laid: thanks to the American National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), cryptographers from around the globe came together to select the best quantum-safe alternatives, culminating in the publication of the first standards in August 2024. These are the new algorithms that the vast majority of users will adopt.

Unfortunately, many governments and enterprises run a great amount of legacy software that is hard to update, making this a complex IT migration that can easily take 5-15 years, depending on the organisation. There’s a serious threat that quantum computers will be able to run Shor’s algorithm within such a timeframe, so organisations are encouraged to start migrating as early as possible.

A new type of cryptography comes with its own additional risks: the new standards have not yet been tested as thoroughly as the nearly 50-year-old RSA algorithm. Ideally, new implementations will be hybrid, meaning that they combine the security of a conventional and a post-quantum algorithm. On top of that, organisations are encouraged to adopt cryptographic agility, meaning that cryptosystems can be easily changed or updated if the need arises.

Read more: What steps should your organisation take?

3. Quantum Key Distribution to strengthen cryptography

Out of all the applications for quantum networks, Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) is the one to watch. It allows two parties to generate secure cryptographic keys together, which can then be used for everyday needs like encryption and authentication. It requires a quantum network connection that transports photons in fragile quantum states. Such connections can currently reach a few hundred kilometres, and there is a clear roadmap to expand to a much wider internet. The most likely usage will be as an ‘add-on’ for high-security purposes (such as military communication or data exchange between data centres), in addition to standard post-quantum cryptography.

Unfortunately, we often see media articles suggesting that QKD is a solution to the threat of Shor’s algorithm and that it would form an ‘unbreakable internet’. Both claims are highly inaccurate. Firstly, QKD does not offer the wide range of functionality that public key cryptography offers, so it is not a complete replacement for the cryptosystems broken by Shor. Secondly, there will almost certainly be ways to hack a QKD system (just like with any other security system). Then why bother with QKD? The advantage of QKD is based on one important selling point: contrary to most other forms of cryptography, it does not rely on assumptions about the computational power of a hacker. This can be an essential factor when someone is highly paranoid about their cryptography or when data has to remain confidential for an extremely long period of time.

At this time, pretty much every national security agency discourages the use of QKD simply because the available products are far from mature (and because PQC should be prioritised). It is unclear how successful QKD could be in the future—we will discuss this in-depth in another chapter.

We firmly warn that other security products with the word ‘quantum’ in the name do not necessarily offer protection against Shor’s algorithm. In particular, quantum random number generators (QRNGs) are sometimes promoted as a saviour against the quantum threat, which is nonsense. These devices serve a completely different purpose: they compete with existing hardware to generate unpredictable secret keys, which find a use (for example) in hardware security modules in data centres.

Read more: What are the use cases of quantum networks?

See also:

4. Optimisation and machine-learning

This is the part where most enterprises get excited. Can we combine the success of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning with the radically new capabilities of quantum computers? Can we create a superpowered version of ChatGPT or DALL-E, or at least speed up the demanding training process?

In this section, we’ll take a closer look at the known applications for quantum computers on ‘non-quantum problems’ other than cryptography. We focus specifically on the harder optimisation problems that currently take up large amounts of classical resources. Under the hood, all such applications are based on concrete mathematical problems such as binary optimisation, differential equations, classification, optimal planning, and so forth. For conciseness, we will use the word ‘optimisation’ as a catch-all term for all these problems, including things like machine learning and AI.

Unfortunately, the amount of value that ‘quantum’ can add to optimisation tasks is very much a disputed topic. The situation here is very subtle: there exist many promising quantum algorithms, but as we’ll see, each comes with important caveats that might limit their practical usefulness. To start, we can classify the known algorithms into the following three categories.

Rigorous but slow algorithms

Many quantum optimisation algorithms have a well-proven quantum speedup: there is no dispute that these require fewer computational steps than any classical algorithm. For instance, a famous quantum algorithm invented by Lov Grover (with extensions by Dürr and Høyer) finds the maximum of a function in fewer steps than conventional brute-force search. Similarly, quantum speedups were found for popular computational methods such as backtracking, gradient descent, linear programming, lasso, and for solving differential equations.

The main question is whether this also means that the quantum computer requires less time! All of the above optimisation algorithms offer a so-called polynomial speedup (in the case of Grover, this is sometimes further specified to be a quadratic speedup). As we will soon see, it is not entirely clear if these speedups are enough to compensate for the slowness of a realistic quantum computer – at least in the foreseeable future.

Heuristic algorithms

Some algorithms claim much larger speedups, but there is no undisputed evidence to back this up. Often, these algorithms are tested on small datasets using the limited quantum computers available today – which are still so tiny that not much can be concluded about larger-scale problems. Nonetheless, these ‘high risk, high reward’ approaches typically make the bold claims that receive media attention. The most noteworthy variants are:

Variational quantum circuits (VQC) are relatively short quantum programs that a classical computer can incrementally change. In jargon, these are quantum circuits that rely on a set of free parameters. The classical computer will run these programs many times, trying different parameters until the quantum program behaves as desired (for example, it might output very good train schedules or accurately describe a complex molecule). The philosophy is that we squeeze as much as possible out of small quantum computers with short-lived qubits: the (fast) classical computer takes care of most of the computation, whereas the quantum computer runs just long enough to sprinkle some quantum magic into the solution.

Although its usefulness is disputed, this algorithm is highly flexible, leading to quantum variants of classifiers, neural networks, and support vector machines. Variants of this algorithm may be found under different names, such as Quantum Approximate optimisation Algorithm (QAOA), Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), and quantum neural networks.Quantum annealing solves a particular subclass of optimisation problems. Instead of using the conventional ‘quantum gates’, it uses the native physical forces that act on a set of qubits in a more analog way.

Annealing itself is a mature classical algorithm. The advantage of a ‘quantum’ approach is not immediately apparent, although there are claims that hard-to-find solutions are more easily reached thanks to ‘quantum fluctuations’ or ‘tunnelling’.

Quantum annealing was popularised by the Canadian company D-Wave, which builds dedicated hardware with up to 5000 qubits and offers a cloud service that handles relatively large optimisation problems.

Fast algorithms in search of a use case

Finally, there exist algorithms with large speedups, for which we are still looking for applications with any scientific or economic relevance. These are classic cases of solutions in search of a problem. The most notable example is the quantum algorithm that solves systems of linear equations2 with an exponential advantage. This problem is ubiquitous in engineering and optimisation, but unfortunately, there are so many caveats that no convincing practical uses have been found3.

Recently, much attention has gone to the algorithm for topological data analysis (a method to assess certain global features of a dataset), which promises an exponential advantage under certain assumptions. Again, scientists are still searching for a convincing application.

Similarly, a quantum version of a classical machine learning algorithm called Support Vector Machines was found to have an exponential advantage over classical methods4. Unfortunately, this only works with a very specific dataset based on the factoring problem that Shor’s algorithm is well known for. No rigorous advantage is known for more general datasets.

A fourth class: quantum-inspired algorithms

Some impressive speedups that were recently found have been ‘dequantised’: these algorithms were found to work on classical computers too! There’s a beautiful story behind this process, where Ewin Tang, an undergraduate student at the time, made one of the most unexpected algorithmic breakthroughs of the decade. A great report by Robert Davis can be found on Medium5.

What’s left?

Unfortunately, a quantum optimisation algorithm with undisputed economic value does not yet exist; all of them come with serious caveats. This perspective is perhaps a bit disappointing, especially in a context where quantum computing is often presented as a disruptive innovation. Our main takeaway is that quantum optimisation (especially quantum machine learning!) is rather over-hyped.

That doesn’t mean that there’s no hope for quantum optimisation. Firstly, there are good reasons to believe that new algorithms and applications will be found. Secondly, the usefulness of the ‘slower’ quantum optimisation algorithms ultimately depends on the speed of a future quantum computer compared to the speed of a future classical computer. To better understand the differences in computational speeds, we will need to quantify the amount of ‘quantum advantage’ that different algorithms have.

Read more: Optimisation and AI: what are companies doing today?

How can we compare different types of speedups?

When looking at the applications of quantum computers, one should always keep in mind: Are these actual improvements over our current state-of-the-art? Anyone can claim that their algorithm can solve a problem, but what we really care about is whether it solves it faster. Classical computers are already extremely fast, so quantum algorithms should offer a substantial speedup before they become competitive.

The fairest way to compare algorithms is by running them on actual hardware in a setting similar to how you would use the algorithm in practice. In the future, we expect such benchmarks to be the main tool to compare quantum and classical approaches. However, mature quantum hardware is not available yet, so we resort to a more theoretical comparison tool: the asymptotic runtime of an algorithm.

What does asymptotic runtime mean?

An important figure of merit of an algorithm is its so-called asymptotic complexity, which describes how much longer a computation takes as the problem becomes ‘bigger’ or more complicated. The term ‘asymptotic’ refers to the problem’s size, which gets (asymptotically) larger, theoretically all the way to infinity.

Size turns out to be a very relevant parameter. For example, computing 54 x 12 is much easier than 231.423 x 971.321, even though in technical jargon, they are instances of the same problem of ‘multiplication’, and we’d use the very same long multiplication algorithm that we learned in elementary school to tackle them. Similarly, creating a work schedule for a team of 5 is simpler than dealing with 10,000 employees. We typically use the letter \(n\) to denote the problem size. You can see \(n\) as the number of digits in a multiplication (like 2 or 6 above) or the number of employees involved in a schedule.

For some very hard problems, the time to solution takes the form of an exponential, something like \(T\ \sim\ 2^{n}\) or \(T\ \sim\ 10^{n}\), where \(T\) is the number of steps (or time) taken6. Exponential scaling is typically a bad thing, as such functionsss becomes incredibly large even for moderate values of \(n\). For example, brute-force guessing a pin code of \(n\) digits takes roughly \(T\ \sim\ 10^{n}\).

There are also problems for which the number of steps scales like a polynomial, such as \(T\ \sim\ n^{3}\) or \(T\ \sim\ n\). Polynomials grow much slower than exponentials, allowing use to solve large problems in a reasonable amount of time. Whenever a new algorithm can bring an exponential scaling down to a polynomial, we may call this an ‘exponential speedup’. Such speedups are a computer scientist’s dream because they have a tremendous impact on practical runtimes. For example, quantum computers can factor large numbers in time roughly \(T\ \sim\ n^{3}\) (thanks to Shor’s algorithm7), whereas the best classical algorithm requires close to exponentially many steps8.

Often, we deal with ‘merely’ a polynomial speedup, which happens when we obtain a smaller polynomial (for example, going from \(T\ \sim\ n^{2}\) towards \(T\ \sim\ n\) or perhaps even a ‘smaller’ exponential function (like \(T\ \sim\ 2^{n}\) towards \(T\ \sim\ 2^{n/2}\)). Reducing the exponent by a factor of two (like \(n^{2}\ \rightarrow n\)) is also sometimes called a quadratic speedup, which is precisely what Grover’s algorithm gives us.

See also:

- At a more coarse level, we can define different complexity classes like P, NP and BQP.

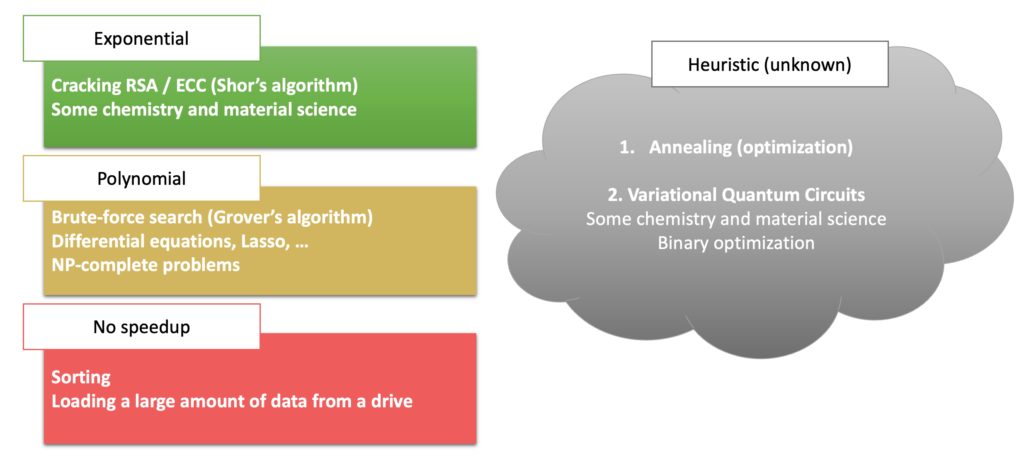

Here is a rough overview of quantum speedups as we understand them today, categorised by their type of asymptotic speedup:

🟢 The ‘exponential’ box is the most interesting one, featuring applications where quantum computers seem to have a groundbreaking advantage over classical computers. It contains Shor’s algorithm for factoring, explaining the towering advantage that quantum computers have in codebreaking. We also believe it contains some applications in chemistry and material science, especially those relating to dynamics (studying how molecules and materials change over time).

🟡 The ’polynomial’ box is still interesting, but its applicability is unclear. Recall that a quantum computer would need much more time per step – and on top of that, it will have considerable overhead due to error correction. Does a polynomial reduction in the number of steps overcome this slowness? According to a recent paper, small polynomial speedups (as achieved by Grover’s algorithm) will not cut it, at least not in the foreseeable future.

🔴 For some computations, a quantum computer offers no speedup. Examples include sorting a list or loading large amounts of data.

If this were the complete story, then most people would agree that quantum computing is a bit disappointing. It would be a niche product for hackers and a tiny community of physicists and chemists who study quantum mechanics itself.

⚪ Luckily, there is yet another category: many of the most exciting claims come from the heuristic algorithms. This term is used when an algorithm might give a suboptimal solution (which could still be useful) or when we cannot rigorously quantify the runtime. Such algorithms are quite common on classical computers: neural networks fall in this category, and these caused a significant revolution in AI. Unfortunately, it is unclear what the impact of currently known heuristic quantum algorithms will be.

In summary, the potential for a useful quantum speedup varies greatly across applications, and so does their range of applicability. The case of factoring has a clear and convincing speedup but provides little value except to those with malicious intent. In contrast, machine learning and optimisation do tackle a broad palette of relevant problems, but the speed advantage of a quantum computer remains uncertain in this field. The applications of chemistry and material science fall somewhere in the middle, with some relevant areas of applicability and concrete indications of a practical speed advantage.

Where is the killer application?

Is there hope that we’ll find new quantum algorithms with a large commercial or societal value? For a quantum algorithm to be truly impactful, we require two properties:

[Useful] The algorithm solves a problem with real-world significance (for example, because organisations can work more efficiently or because it helps answer a scientific question).

[Better/faster] Using this particular algorithm is the most sensible* choice from a technical perspective**, even when compared to all other possible methods.

I’d propose the term quantum utility for a situation where both properties are convincingly satisfied.

The precise definition can be a bit finicky, so before we start searching for utility, we need to get some technical details out of the way.

* What is ‘sensible’ (2) depends strongly on the context of the real-world problem (1). In most cases, we care about how fast a problem is solved, but one should also take into account the total cost of developing the software, the cost of leasing the hardware, the energy consumption, the probability of errors, and so forth. For example, a high-frequency trader might be happy with a 2% faster algorithm even if the costs are sky-high and there’s a decent chance of failure, whereas a hospital could dismiss a 200x faster quantum approach if the costs don’t outweigh the benefits. Indeed, what is ‘sensible’ is highly subjective. In practice, we can relax this requirement somewhat and focus primarily on speed, which is a sufficiently complex figure of merit. Ideally, the quantum algorithm should enjoy an exponential speedup or at least a large polynomial speedup.

** We explicitly look for technical perspectives. Otherwise, one might also say that using a quantum algorithm is commercially the best option because it creates good PR or because it keeps the workforce excited. Then perhaps the first utility has already been reached! However, this is not the computational revolution that we’re looking for, so I explicitly exclude such non-technical reasons in property (2). Similarly, I don’t want to worry too much about legal issues (‘it doesn’t comply with regulations’) because it feels somewhat artificial to dismiss a quantum algorithm for such reasons.

Supremacy, advantage, utility

Around 2019 and 2020, the terms quantum supremacy and quantum advantage were popularly used when quantum computers did, for the first time, beat the best supercomputers in terms of speed (property 2)9 10. This involved an algorithm that was cherry-picked to perform well on a relatively small and noisy quantum computer whilst being as challenging as possible for a conventional supercomputer. Quantum advantage was mostly a man-on-the-moon-type scientific achievement, showcasing the rapid progress in hardware engineering and silencing the sceptics who still thought quantum computing wouldn’t work. There was no attempt to have any practical value (1).

As a natural next step, the race is on to be the first to run something useful whilst leaving classical supercomputers in the dust. This led IBM to coin the term quantum utility11, which we adapted above. In the following years, we can expect the leading hardware and software manufacturers to maximise the amount of ‘utility’ that they could possibly squeeze out of medium-sized quantum computers, whilst competitors will use their best classical simulations to dispute these claims. The first battles have already been fought: in June 2023, IBM claimed to simulate certain material science models better than classically possible12, quickly followed by two scientific responses that showed how easy it was to simulate the same experiment on a laptop13 14.

It seems to me that healthy competition is good for the field overall. It should lead to increasingly convincing and rigorous quantum utility, from which the end-users will eventually profit!

In parallel, there is a rapidly expanding number of press releases by startups and enterprises that claim to create business value by solving industrial problems on today’s hardware, often without sharing many details. These approaches typically start with a relevant problem in mind and hence score well on usefulness (1). However, it is questionable whether quantum algorithms were indeed the best option (2), and most reports I’ve seen hardly bother to show any argumentation in this direction. Such claims should only be taken seriously if a rigorous benchmark against state-of-the-art classical techniques is included.

Do known algorithms provide utility?

With the quantum utility criteria in mind, we can revisit the algorithms that were discussed before.

| (1) Useful | (2) Better than classical | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimisation: Rigorous but slow algorithms | ✓ | ? |

| Optimisation: Fast algorithms in search of a use casess | ? | ✓ |

| Optimisation: Heuristic algorithms | ✓ | ? |

| Simulation of molecules and materials | ✓ | ? |

| Breaking RSA | ✓ | ✓ |

Several algorithms, most notably Grover’s algorithm, have an extensive range of industrial applicability. However, it seems that in practice, other (classical) approaches solve such problems faster. The quadratic speedup will be insufficient in the near term, and it’s unclear if it will be in the future.

Then, we have several exponential speedups, like the algorithm for topological data analysis, for which no practical uses have been found (despite many scientific and industrial efforts).

Most optimistic outlooks focus on heuristic algorithms, for which the speed advantage will become clear with maturing hardware.

Even for simulation of molecules and materials, it is hard to pinpoint precisely where we can find utility. Classical computers are already incredibly fast, and excellent classical algorithmic techniques have been developed. Scientist Garnet Chan even gives talks which are suggestively titled ‘Is There Evidence of Exponential Quantum Advantage in Quantum Chemistry?’. The case for chemistry and material science is quite subtle, and we discuss this further in the in-depth chapter on quantum simulation.

To our best knowledge, codebreaking (Shor’s algorithm) is the only impactful algorithm that has little competition from classical methods. Hopefully, most critical cryptography will be updated well before a quantum computer arrives, making large-scale deployment of Shor’s algorithm relatively uninteresting. Either way, the application of codebreaking is not quite the positive innovation that quantum enthusiasts are looking for.

Could the nature of quantum mechanics be such that exponential speedups are only found in codebreaking, chemistry, and a bunch of highly artificial toy problems, but nowhere else in the broad spectrum of practically relevant challenges? Most people would argue that such a scenario is unlikely. There are still good hopes that either some of the caveats with existing algorithms will be addressed or that new breakthrough algorithms will be discovered.

How optimistic you are about quantum computing should depend on (at least) the following questions:

- How impactful will heuristic and to-be-discovered algorithms be compared to classical algorithms? In other words, what is the algorithmic potential of quantum computing?

- How will quantum hardware develop relative to classical hardware?

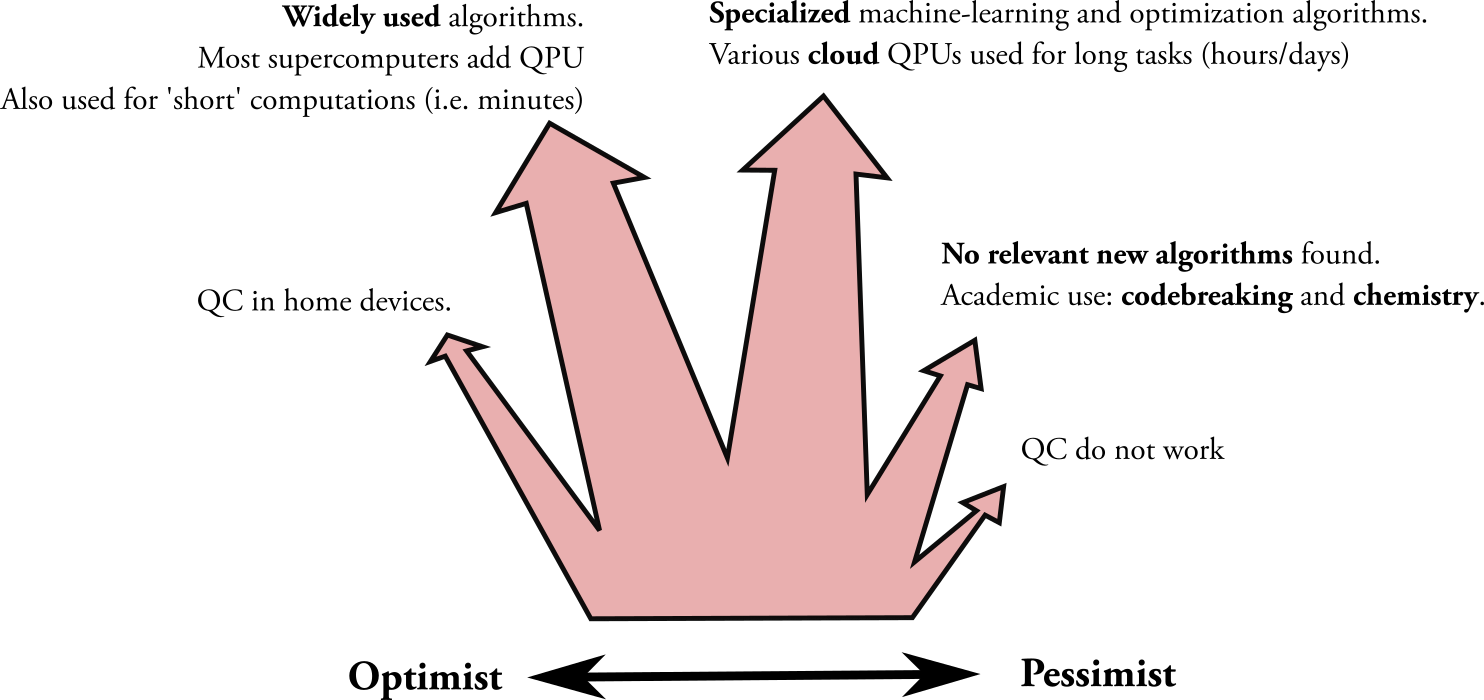

Ultimately, the commercial success of quantum computers depends strongly on these questions. If we allow ourselves to do some more hypothetical dreaming, I picture that the following future scenarios could be possible, on a spectrum of optimism versus pessimism:

Starting on the pessimistic side, if one believes that optimisation algorithms turn out to be lacklustre, then quantum computing might remain a niche for academics. However, depending on the utility of more widely applicable algorithms, it could be that quantum computers will be installed in special-purpose computing facilities or, even more optimistically, that they become increasingly common additions to data centres (much like GPUs today). Where would you place yourself in this figure?

Further reading

‘The Potential Impact of Quantum Computers on Society‘15 (Ronald de Wolf, 2017) is an accessible overview of known algorithms, together with an assessment of how we can ensure a mostly positive net effect on society.

‘Quantum algorithms: an overview‘16 (Ashley Montanaro, 2016) is a more technical overview paper that describes a selection of impactful algorithms in greater detail.

Professor Scott Aaronson warns us to ‘Read the fine print’ of optimisation algorithms. [Appeared in Nature Physics, with paywall]

A quantitative analysis of Grover’s runtime compared to today’s supercomputers.

(Scientific paper) Amazon researchers lay out a comprehensive list of end-to-end complexities of nearly every known quantum algorithm.

Jordan, S. (2024) Quantum Algorithm Zoo. Available at: https://quantumalgorithmzoo.org/ (Accessed: 27 September 2024). ↩

Harrow, Aram W; Hassidim, Avinatan; Lloyd, Seth (2008). ‘Quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations’. Physical Review Letters. 103 (15) 150502. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.150502 ↩

Aaronson, Scott. ‘Read the Fine Print.’ Nature Physics 11, no. 4 (April 2015): 291–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3272. Open access: https://www.scottaaronson.com/papers/qml.pdf. ↩

Liu, Yunchao, Srinivasan Arunachalam, and Kristan Temme. ‘A Rigorous and Robust Quantum Speed-up in Supervised Machine Learning.’ Nature Physics 17, no. 9 (September 2021): 1013–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-021-01287-z. ↩

Qiskit. ‘How Ewin Tang’s Dequantized Algorithms Are Helping Quantum Algorithm Researchers.’ Qiskit (blog), March 15, 2023. https://medium.com/qiskit/how-ewin-tangs-dequantized-algorithms-are-helping-quantum-algorithm-researchers-3821d3e29c65. ↩

With the symbol \(\sim\) we mean ‘roughly proportional to’. It essentially allows us to write down an approximation of a function, making them easier to read, throwing away some details are not important here. ↩

You may find even sources stating that Shor’s algorithm takes a time proportional to n2 log(n). Such scaling is theoretically possible but relies on asymptotic optimisations that are unlikely to be used in practice. ↩

Technically, the best algorithms for factoring, like the general number field sieve, have a scaling behavior that lies between polynomial and exponential. Hence, the speedup of Shor’s algorithm is technically a bit less than ‘exponential’ – a more correct term would be ‘superpolynomial’. Still, this book (and many other sources) continue to use the term ‘exponential speedup’ to emphasize the enormous scaling advantage over polynomial speedups. ↩

Han-Sen Zhong et al., Quantum computational advantage using photons. Science 370, 1460-1463 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe8770 ↩

Arute, Frank, Kunal Arya, Ryan Babbush, Dave Bacon, Joseph C. Bardin, Rami Barends, Rupak Biswas, et al. ‘Quantum Supremacy Using a Programmable Superconducting Processor’. Nature 574, no. 7779 (October 2019): 505–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5. ↩

Technically, IBM has a subtly different interpretation. In a blog post (see https://www.ibm.com/quantum/blog/what-is-quantum-utlity), they define ‘utility’ as: ‘Quantum computation that provides reliable, accurate solutions to problems that are beyond the reach of brute force classical computing methods, and which are otherwise only accessible to classical approximation methods.’ In other words: a quantum computer doesn’t have to outperform any classical algorithm, it merely has to compete with the silly approach of brute-force search – which is almost never the best algorithm in practise. This definition seems heavily focused on claiming utility as soon as possible. Nevertheless, if we look at the big picture, we seem to have a similar notion of ‘advantage for end-users’ in mind, so I’m happy to adopt the term ‘utility’ anyway. ↩

Kim, Youngseok, Andrew Eddins, Sajant Anand, Ken Xuan Wei, Ewout van den Berg, Sami Rosenblatt, Hasan Nayfeh, et al. ‘Evidence for the Utility of Quantum Computing before Fault Tolerance’. Nature 618, no. 7965 (June 2023): 500–505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06096-3. ↩

Begušić, Tomislav, and Garnet Kin-Lic Chan. ‘Fast Classical Simulation of Evidence for the Utility of Quantum Computing before Fault Tolerance’. arXiv, 28 June 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.16372. ↩

Tindall, Joseph, Matthew Fishman, E. Miles Stoudenmire, and Dries Sels. ‘Efficient Tensor Network Simulation of IBM’s Eagle Kicked Ising Experiment’. PRX Quantum 5, no. 1 (23 January 2024): 010308. https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.5.010308. ↩

de Wolf, R. (2017) ‘The potential impact of quantum computers on society’, Ethics and Information Technology, 19(4), pp. 271–276.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-017-9439-z. (Open access: https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.05380) ↩

Montanaro, A. (2016) ‘Quantum algorithms: an overview’, npj Quantum Information, 2(1), pp. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjqi.2015.23. ↩