The impact on cybersecurity

Reading time: 13 minutes

Contents

- Cryptography is much more than just secrecy

- The quantum threat is mainly to public key cryptography

- What solutions exist?

- Conclusion

- Further reading

In the world of quantum computers, the most convincing exponential speedup lies in codebreaking. Anyone who wants to understand the impact of quantum computers must know the basics of cryptography. Let’s start at the beginning.

Cryptography is much more than just secrecy

Why do we actually use cryptography? Pretty much everyone will immediately think of:

- Privacy/confidentiality: ensuring others cannot read your data (especially when messages are sent over a network).

However, there are many more threats that cryptography protects us from. Most people wouldn’t normally worry about them, but when any of the following is missing, cybercriminals can cause a lot of harm:

Authentication/identification: You want to verify that a message really came from the entity that claims to send the message. For example, during online banking, you want to be 100% sure that you are communicating with your bank and nobody else.

Another example is when installing a new piece of software. When executing the latest Windows update, your computer makes sure to check that there is a ‘digital signature’ that belongs to Microsoft. Imagine how unsafe your laptop would be if anyone could send fake updates!Integrity: You want to verify that nobody changed the message during transit. Imagine the damage when anyone can alter emails or file transfers, or when the commands coming from an air traffic control tower are modified. Similarly, any software installer confirms that the software wasn’t changed by anyone but the original publisher, by verifying a digital signature.

Exchanging secret keys: How do you negotiate a new secret key with a brand new web shop that you have never visited before? This is a seemingly impossible task if anyone can read bare internet traffic, but modern cryptography has a solution.

There are many other vital functionalities, like non-repudiation and availability, that we don’t discuss here. Remember the bold-faced terms above, as we will often come across these.

We hope that this introduction makes you aware of the enormous importance of proper cryptography and the sheer number of cryptographic checks required for the proper functioning of our IT. You would be surprised how often you use cryptography on a daily basis through your laptop, phone, car keys, or smart cards.

The quantum threat is mainly to public key cryptography

A common misconception, which we see a lot in popular literature, is that the quantum threat can be summarised as follows. (Both of the statements below are incorrect!)

‘A quantum computer will break all of today’s cryptography.’

‘A quantum internet is needed to keep our cryptography safe again.’

To better understand this, let’s first look at what cryptography a quantum computer will break, and which it won’t. Later, we will look at the necessity of a quantum internet.

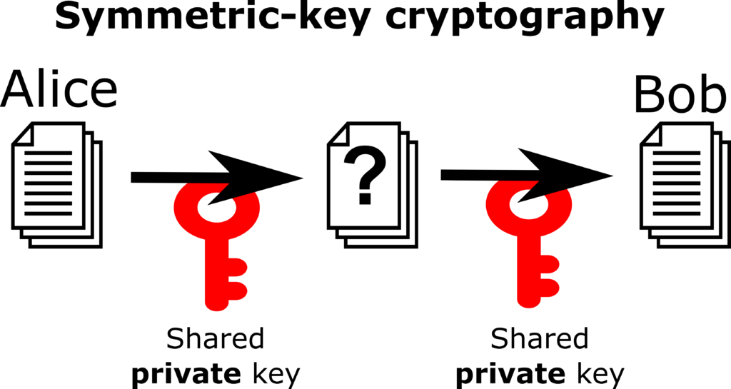

In line with common cryptography jargon, we will typically have two parties, Alice and Bob, who want to communicate with each other. We distinguish two different types of cryptography: the symmetric and the asymmetric (public key) variants.

In symmetric (or private key) cryptography, we assume that both Alice and Bob already know some secret key. This could be a password that they both know or, more commonly, a very long number represented by (say) 128 bits in their computer memory. Alice can use the key to encrypt any message using a cipher like AES. Bob can then use the same key to decrypt this message. The details of how encryption and decryption work are unimportant for our purposes. The only relevant thing is that our computers can do this very efficiently and that it’s considered sufficiently safe: without the key, nobody could reasonably break this encryption.

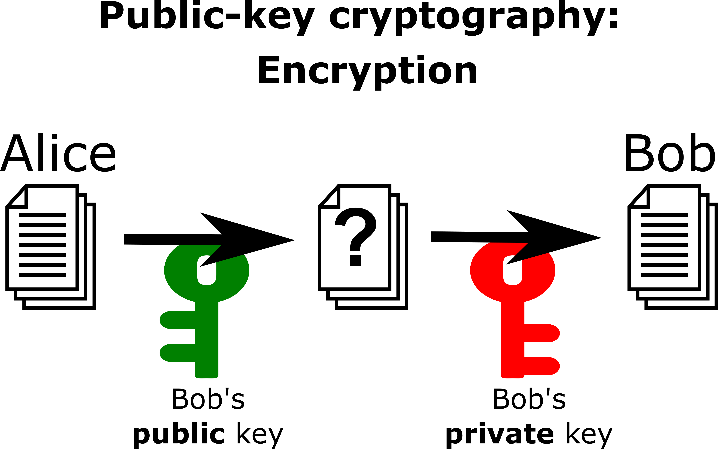

In asymmetric cryptography, more often called public key cryptography (PKC), each participant has two keys: a public key and a private key. The public key can be shared with anyone, while the private key must be kept secret. That’s why we use the suggestive colours green (save to share) and red (keep private!). If Alice wants to send an encrypted message to Bob, she uses Bob’s public key to encrypt the message. The message can only be decrypted using Bob’s private key, ensuring that only Bob can read the message.

The setting with two keys offers more functionality. For example, using public key cryptography, Alice could securely send a secret key to Bob that they can subsequently use for symmetric cryptography, which is faster in practice. When public key cryptography is built for this purpose, we call it a key encapsulation mechanism (KEM).

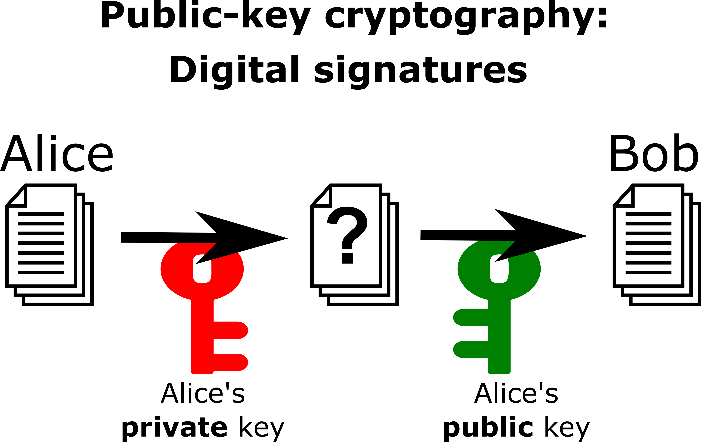

Furthermore, the protocol works in ‘reverse’. Alice can use her private key to encrypt a message, which then anyone in the world (including Bob) can decrypt using the corresponding public key. Bob should then be confident that Alice is the only person who could have encrypted this message. Indeed, something encrypted with the private key can only be decrypted with the public key, and vice versa. The encrypted message is much like a signature that only Alice can produce. This forms the basis of digital signatures and certificates.

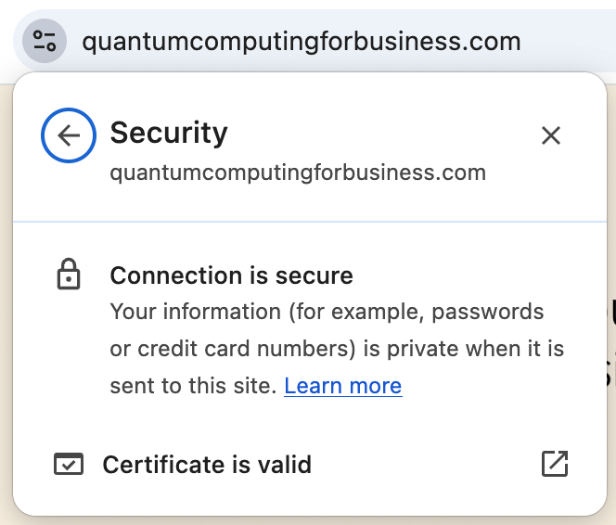

You can see public key cryptography in action whenever you visit a web page. Your browser (like Chrome or Firefox) will display that the connection is secure, which means that it verified that the digital signature is valid, amongst other things. This guarantees authenticity (the page came from a registered server) and integrity (the site arrived unchanged).

It should come somewhat as a surprise that public key cryptography is even possible at all! It’s kind of a small miracle that encryption and decryption with two totally different keys can be made to work, thanks to some powerful mathematics. However, it turns out that the delicate relationship between the two keys is also a weak spot…

How good are quantum computers at cracking cryptography?

Symmetric-key cryptography is quite safe against quantum hackers. The biggest problems are brute-force attacks, where an attacker effectively tries every possible secret key. Using a key size of 128 bits, the total number of possible keys is 2128 — that’s an incomprehensibly large number, much more than the number of atoms in a human body.

We know that Grover’s algorithm speeds up brute-force search by reducing the number of attempts from 2128 to its square root, which is 264. This is something that cryptographers are not happy about, but considering the slowness and extra overhead that comes with quantum computers, this doesn’t seem to be a problem in the foreseeable future. Still, to be on the safe side, it is recommended to double key lengths, hence, to use the same algorithm with 256-bit keys. Changing this in existing IT infrastructure is relatively straightforward, although one shouldn’t underestimate the time and costs for such changes within large organisations.

The situation is entirely different with public key cryptography. The most-used algorithms today, RSA and ECC, can be straightforwardly broken by a large quantum computer. We discussed the details of Shor’s algorithm earlier and saw that around 20 million qubits and 8 hours are needed to retrieve a secret RSA key. Luckily, there exist PKC systems that are believed to be safe against quantum computers, and an obvious way forward is to start using these. We call such systems post-quantum cryptography, and despite the confusing name, they’re built to work on conventional computers. We discuss the rabbit hole of migrating to new cryptography in a different chapter.

Unfortunately, even today’s communication could be at risk due to a practice called harvest now, decrypt later. Encrypted messages that are sent over a network can be intercepted and stored for many years, until a quantum computer can efficiently decrypt the messages. Even though we use public key encryption mainly to establish temporary keys for symmetric cryptography, a smart attacker could still retrace all the intermediate steps and retroactively spy on our communication. It is unclear at what scale storage of sufficiently detailed internet data is genuinely happening, but it seems plausible that security agencies of larger nations are already doing this.

The following table summarises how our cryptosystems are threatened:

| Symmetric | Public-key | Quantum networks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Today (AES, … ) | Today (RSA, ECC) | PQC | QKD | |

| Safe against classical computers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Safe against quantum computers | ✔* *with double key lengths | Unsafe | ✔ | ✔ |

Why don’t we switch to symmetric cryptography?

Public key cryptography solves a very fundamental problem: how can Alice and Bob agree on a secret key before they have a means of encryption in the first place? They cannot just send a new key over the internet without any form of encryption, because anyone would be able to read this. This is the fundamental problem of key distribution. Let us look at the functionality offered by the two types of cryptography:

| Symmetric | Public-key | Quantum key distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidentiality (privacy) | Only with pre-shared keys | ✔ | ✗ |

| Authentication / Integrity | Only with pre-shared keys | ✔ | ✗ |

| Establishing secret keys | ✗ | ✔ | ✔* *Only when another mechanism takes care of authentication. |

If only we could somehow give Alice and Bob pre-shared keys in a secure way, we would resolve most of these problems. Without public key cryptography, there are other options:

Trusted courier. Alice and Bob could meet every other week to exchange USB drives with secret codes.

Trusted third party. Alice and Bob could both trust a large ‘key server’. If both share a secret key with the key server, they can securely ask the server to generate a new secret key that they can use together.

Quantum key distribution. We discuss this solution further below.

Unfortunately, trusted couriers or trusted third parties are rarely an attractive alternative to public key cryptography, especially when scaling up to networks with thousands or millions of connected users. Couriers are simply too slow for today’s standards, and single trusted parties would pose a particularly interesting target for attackers.

What solutions exist?

There is a clear need for post-quantum cryptography to replace commonly used cryptosystems like RSA and ECC. Luckily, back in 2016, the American National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) started a competition to select a new cryptosystem which should balance safety and practical usability (for example, it should not be too slow or memory-inefficient). They invited experts from around the globe to propose cryptographic algorithms, which peers assessed. Four rounds and several broken algorithms later, NIST selected a first set of winners that are suitable for large-scale use. As of August 2024, the first three PQC algorithms are now official NIST standards.

Even though this effort was coordinated by an American institute, the process was backed and carried out by cryptographers from around the world. A broad majority of cybersecurity experts have confidence in NIST’s competition and recommend the final standards. National security organisations from other countries like BSI (Germany) and ANSSI (France) may prefer different algorithms but have also explicitly stated that this does not mean that they consider NIST’s standards unsafe.

The results of the competition are as follows. Firstly, NIST selected one Key Encapsulation Mechanism that can be used to establish secret keys over an unencrypted connection - remember the problem of communicating with a web shop that you had never encountered before.

| Functionality | NIST Name | Problem family | Documentation | Original name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Encapsulation Mechanism | ML-KEM | Module-Lattice based | FIPS 203 | CRYSTALS-Kyber |

Secondly, NIST selected three different Digital Signature Algorithms. These are used for authentication and integrity – remember how we don’t want our messages to be altered in transit or how we want to prevent malware injected in software updates.

| Functionality | NIST Name | Algorithm family | Documentation | Original name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Signatures Algorithm | ML-DSA | Module-Lattice based | FIPS 204 | CRYSTALS-Dilithium |

| Digital Signatures Algorithm | SLH-DSA | Stateless Hash-Based | FIPS 205 | SPHINCS+ |

| Digital Signatures Algorithm | FN-DSA | Fast-Fourier Transform over NTRU-Lattice based | FIPS 206 (coming soon) | FALCON |

You might wonder why three algorithms were selected. Unfortunately, all three standards come with downsides, for example, because the keys can take up more memory or because the performance (time to sign or verify) is worse. The real-world impact will differ per use case. ML-DSA is the main cryptosystem recommended for general use, whereas SLH-DSA and FN-DSA may be beneficial in specific circumstances.

Are the new standards considered safe?

The short answer is yes: the new PQC standards are considered ready for use, and choosing algorithms such as ML-KEM or ML-DSA is widely regarded as a sound decision. There may be exceptions in specific high-security scenarios, but if you are operating in such a context, you are likely already aware of these nuances.

However, there seems to be some uncertainty within the cryptographic community regarding whether the new PQC standards will be as reliable as our trusted RSA or ECC. The new standards have not yet stood the test of time, and it is possible that unexpected weaknesses—whether minor implementation flaws or fundamental vulnerabilities—may still be present. To illustrate, a PQC method called SIKE1 was in the race to become a new NIST standard and made it all the way to the 4th round until it was proven unsafe.

To mitigate any unexpected vulnerabilities in the new standards, most authorities recommend a hybrid implementation that combines the strengths of both conventional and post-quantum PKC. Moreover, organisations are generally advised to invest in cryptographic agility, a broad term used to describe the ability to easily update cybersecurity defences.

The above may sound somewhat negative, but we don’t expect the slightly lower trust to stand in the way of adoption. Cryptographic algorithms themselves are rarely the weakest point, so it seems wise to focus on other potential vulnerabilities instead.

What about Quantum Key Distribution (QKD)?

Quantum key distribution is also presented as a solution for key exchange, making it a potential alternative to RSA, ECC and ML-KEM.

Still, many security authorities warn against adopting QKD today. Although the idea is promising, today’s hardware is still immature. Moreover, QKD doesn’t provide any functionality for digital signatures, thus we will need the migration to PQC anyway.

It is somewhat of a pity that QKD is not so mature yet, because it would be a viable weapon against Harvest Now, Decrypt Later. Nevertheless, since a quantum threat could be here as soon as the early 2030s, experts warn that companies and governments should fix their PQC first. At a later stage, QKD can be considered as an add-on for further security.

What about Quantum Random Number Generators (QRNG)?

Good random number generators are exceptionally important in cryptography, and QRNGs could provide a good alternative to the hardware random number generators that are widely used today.

However, all they do is generate random numbers – that doesn’t make any protocol in itself quantum-safe. As a general warning: products with ‘quantum’ in the name do not automatically protect against Shor’s algorithm!

What steps should a typical company or government take?

We dedicate a separate chapter to that!

Conclusion

Cryptography is strongly intertwined with quantum computing through Grover’s algorithm, Shor’s algorithm, and Quantum Key Distribution. Security experts recommend that there is an obvious way forward:

Replace current public key cryptography with new, quantum-safe protocols (PQC).

Double key lengths in symmetric cryptography.

Especially the first bullet is a major challenge. There are many legacy systems on the internet that can not be updated so easily. Billions of devices are all interconnected, so updating one device may cause incompatibilities somewhere else. What’s more, PQC protocols will likely require more CPU power, memory, and bandwidth than today’s trusted methods. Companies may need to update the core code of hundreds or even thousands of applications. And lastly, the new protocols haven’t been tested as extensively as our conventional methods, so it is not unlikely that new security issues will be found. Before they are even built, quantum computers are already causing headaches to cryptographers and cybersecurity managers.

Further reading

Cloudflare’s resource page ‘The state of the post-quantum Internet‘ explains many aspects of the migration to post-quantum cryptography.

The NSA publishes recommendations on which cryptographic algorithms should be used and sketches a concrete timeline about when governmental security systems should be updated.

‘The PQC Migration Handbook‘ is a free guide for corporate managers on how to tackle the upcoming cryptography migration, written by Dutch research organisations TNO, CWI and the secret service AIVD.

In the context of Harvest Now, Decrypt Later, the urgency to migrate depends on how long your data should remain confidential, according to Mosca’s Theorem.

Goodin, Dan. ‘Post-Quantum Encryption Contender Is Taken out by Single-Core PC and 1 Hour.’ Ars Technica, August 2, 2022. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/08/sike-once-a-post-quantum-encryption-contender-is-koed-in-nist-smackdown/. ↩