Applications in chemistry and material science

Reading time: 16 minutes

Contents

- What problems in chemistry and material science will we solve?

- Algorithms for quantum chemistry

- A hype around quantum computing for climate change

- A case study of a potential killer application: FeMoco

- Further reading

Perhaps the most credible application of quantum computers is to study quantum physics itself. This helps us deepen our understanding of microscopic systems like molecules, atoms, or even sub-atomic particles, ultimately leading to the discovery of new drugs, materials and chemical production methods. At first sight, there seems to be a significant advantage compared to conventional computers, which struggle to store the complex quantum state of systems with many particles. As far back as 1981, physicist Richard Feynman ended a conference talk with a famous quote, hinting at the opportunities of quantum computing1:

‘I’m not happy with all the analyses that go with just the classical theory, because nature isn’t classical, dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical’.

Since then, scientists have become increasingly adept at accurately controlling quantum systems. Today, universities boast a wide spectrum of analogue quantum experiments that help us understand nature under exotic circumstances. We’re now lining up our tools to take these simulations to the next level: studying nature with digital quantum machines.

In this chapter, we will assess how quantum computers can impact the fields of chemistry and material science. That makes this chapter more technical, and we’ll assume some (very) basic background in chemistry and physics. We discuss the most relevant algorithms, evaluate claims about quantum computing’s benefits in the fight against climate change, and analyse why the nitrogenase enzyme receives such widespread attention.

What problems in chemistry and material science will we solve?

The computational problems that chemists care about typically come in two flavours: static and dynamic problems. The most studied problem is the static variant, where the goal is to find the arrangement(s) of particles with the lowest possible energy. We call such an arrangement the ground state. These states are relevant because we usually find systems in (or close to) their lowest energy states in nature. In the context of molecules, the atomic nuclei are relatively heavy, while the lightweight electrons move much faster and are more prone to be entangled or in a quantum superposition. Therefore, chemists tend to make approximations that allow them to focus primarily on the positions and spins of the electrons: the electronic structure problem.

The other main problem is about dynamics: given some initial configuration of particles, how do they reconfigure themselves after a certain amount of time? This is often referred to as a system’s (time) evolution. Both problems are informally referred to as quantum simulation.

We often receive the question of why it’s so hard to simulate quantum mechanics on a classical computer. Intuitively, this hardness arises when we deal with many particles that exhibit large amounts of superposition and entanglement, such that the location of one particle is heavily dependent on the (undecided) position of many other particles. We call such states strongly correlated. Classical computers struggle because they need to keep track of all the possible locations that particle A can be, but also all the locations of particle B, and the same for particle C, etcetera. As the number of particles grows, the number of possible configurations of these particles increases exponentially. This means that the number of relevant amplitudes (see the chapter on quantum physics) that a classical computer needs to process grows very quickly. Even with a mere one hundred particles, brute-force simulation is far beyond the capabilities of the world’s best supercomputers.

It is a common misconception that quantum computers straightforwardly offer an exponential advantage compared to classical computers for all chemistry problems. An influential recent paper reports2:

‘[…] we conclude that evidence for such an exponential advantage across chemical space has yet to be found. While quantum computers may still prove useful for ground-state quantum chemistry through polynomial speedups, it may be prudent to assume exponential speedups are not generically available for this problem.’

Note that this comment is specifically about finding ground states, which is still arguably the most relevant problem in chemistry. There is still ample evidence that quantum computers offer an exponential speedup for time evolutions.

There is more bad news for quantum computers. Over the years, computational chemists have found brilliant approximations, hacks, and optimisations to work around the classical computer’s bottlenecks, raising a high bar before a quantum computer can meaningfully compete. For nearly every problem in chemistry, there appears to be a clever trick to solve it somewhat efficiently on a classical machine.

For a killer application, we likely need to search in a fairly specific niche, right at the sweet spot where classical methods struggle while a quantum computer excels. It is not entirely clear how large this niche is, and it is an active research area to identify more systems where classical methods fall short. One promising area involves multi-metal systems, where multiple metal ions are close together. Such systems are present in biologically relevant enzymes such as P450 and FeMoco3. Another is in heterogeneous catalysis, where the catalyst and reagents/products are in a different phase of matter4.

The first practical users of quantum simulation algorithms will most likely be scientists who study the fundamentals of quantum systems. Physicists are already employing devices that are very similar to early quantum computers to mimic certain classes of materials. We wouldn’t call these devices computers yet, but rather analogue simulators. One of the first actual applications of a fully digital quantum computer could be to analyse theoretical models of quantum materials, such as the famous Hubbard model5.

The first error-corrected quantum computers will hopefully find their place in industrial R&D settings. One of the first application areas could be to better understand the aforementioned multi-metal systems, which are relevant in the calculations of ligand binding affinities in drugs and in understanding the mechanism behind the biological production of ammonia. We address the latter example at the end of this chapter. Another exciting area could be to explore the mechanism behind Type-II superconductivity and to search for materials that become superconducting at even higher temperatures6. It is hard to say what the impact of quantum computers will be beyond such niche areas, as this will depend strongly on the usefulness of small polynomial speedups and unpredictable breakthroughs in quantum algorithms. We see a broad palette of other impactful applications that have been proposed, such as photocatalytic reactions (for example, efficiently splitting water to produce hydrogen fuel)7, carbon capture mechanisms8, the study of efficient solar cells9 and the development of higher-capacity batteries10.

Algorithms for quantum chemistry

We describe three of the most important quantum simulation algorithms. The first is the Trotter-Suzuki method, sometimes called ‘Trotterisation’, which simulates time evolution. In this case, we assume that some correct initial state of the world is encoded in the qubits of some quantum computer. The Trotter-Suzuki method is guaranteed to return a good approximation of the state at a later time, again encoded in the qubit registers.

The second algorithm is quantum phase estimation (QPE), which reports the energy of a certain quantum state and can be used to produce a system’s ground state. As a subroutine, it requires some time evolution method, like Trotter-Suzuki. Unfortunately, QPE can only provide information about a certain state if it receives an input that is already a reasonable approximation to this state. Especially in the context of describing low-energy configurations, this shifts the problem to producing good candidate ground states.

The most popular algorithm for creating states with certain properties (like very low energies) is the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE). This is an example of a variational quantum circuit: a series of gates that can be gradually changed until the output matches certain requirements. Just like other variational approaches, it is a heuristic algorithm, lacking rigorous guarantees that it will produce the desired output in a reasonable time. However, it is a popular method today thanks to its ease of use and the ability to work with small, noisy computers.

Creating a good approximation to a ground state is, in general, NP-hard. This means that it is extremely unlikely that a rigorous algorithm exists that can find the ground state of any quantum system. On the other hand, there is good hope that more heuristic methods (just like VQE) will be found that work well on certain subsets of systems. In fact, such heuristic methods already form the workhorse of classical computational chemistry, with tools such as Density functional theory (DFT), Configuration Interaction (CI) and Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC). These work for small systems but are often too slow to study large systems such as proteins or drugs11. A workaround is to apply these methods to just a small part of the target system, employing faster but less accurate methods to oversee the larger whole.

An example of a basic workflow to find a ground state on a quantum computer could be as follows. The first step is to train a VQE to output states with low energy12. These might not be the exact ground states, but they will hopefully be very similar (in jargon, they have a large overlap with the ground state). As a second step, we append a QPE circuit, that will not only report the energy of the VQE states, but also has a fair probability of changing these states into perfect ground states (in jargon: it projects onto the ground state). Running the VQE + QPE combination a few times will almost certainly give the lowest energy states, assuming the VQE produces proper approximations of it.

Further reading on simulation algorithms

Various more technical and sophisticated methods exist, for which we refer to other more technical sources. These require expert knowledge of quantum chemistry.

Introduction to Quantum Algorithms for Physics and Chemistry (2012)13, a pedagogical book chapter. Open version: https://arxiv.org/abs/1203.1331.

Quantum Algorithms for Quantum Chemistry and Quantum Materials Science (2020)14, a scientific overview article. Open version: https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.03685.

A hype around quantum computing for climate change

Some businesses make spectacular claims about how quantum computing could be a cornerstone in solving climate change, thanks to the boost to R&D on batteries, carbon capture, and more efficient chemical factories. However, rarely do we see any evidence – most seem to assume that quantum computers simply spit out blueprints for revolutionary sustainable technologies.

McKinsey takes the biscuit with their report titled ‘Quantum computing just might save the planet‘15. The article rightfully selects some of the most impactful technologies to reduce CO2 emissions, like electrification of transport, improved solar panels, and even vaccines that reduce methane emissions by cattle (indeed, due to cow farts). The article concludes that the selected innovations could reduce global warming from 1.7-1.8 °C by 2050 down to just 1.5 °C. It is a mystery to me why they throw in quantum computing because there is no mention whatsoever about why specifically quantum algorithms would be the key enabling factor. This exemplifies what we see more frequently in popular articles: quantum computers are depicted simply as insanely fast computers that will magically solve the barriers to other new technologies on our wishlist.

What are the true prospects for quantum computing in the context of climate change? Sceptics may point out that technological innovations alone will not be sufficient to avert a climate disaster – we will remain agnostic in this debate. A much more concrete issue is the mismatch in timelines. Climate experts agree that, to limit global warming to no more than 1.5° C, we need to take action relatively soon. Imperial College London concludes on their website16, referencing the 2014 IPCC report:

‘Limiting warming to 1.5°C will only be possible if global emissions peak within the next few years, and then start to decline rapidly, halving by 2030.’

Our chapter on timelines shows that it is exceedingly unlikely that significant quantum utility is possible anywhere before the 2030s. Additionally, it will take several years before a computational discovery is sufficiently mature for large-scale deployment. For this reason, we don’t see quantum computers as a good investment against climate change, but rather as a long-term development that can help us tackle other problems that humanity will face in the future.

Do we really have no concrete applications in climate science? Well, we do have some concrete leads. In the search for a killer application in chemistry, perhaps the most-studied topic is the enzyme Nitrogenase. Its active site is precisely a multi-metal system that classical methods struggle with, and as we’ll soon see, it appears in reputable plans for decarbonisation. To understand the relevance of this molecule, we need to dive into the world of food production.

A case study of a potential killer application: FeMoco

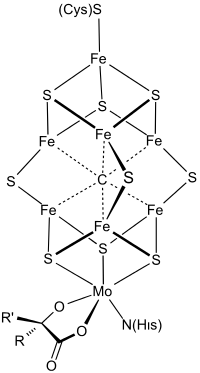

Figure: Chemical structure of the FeMo cofactor of the Nitrogenase enzyme, taken from Wikimedia.

Today’s agriculture relies heavily on the use of artificial fertilisers. Without large-scale use of supplementary nutrients, we would not be able to sustain intensive farming practices and feeding our world’s huge population would be problematic. In fact, about half of the nitrogen atoms in our body have previously passed a fertiliser factory!

Unfortunately, the production of fertiliser involves enormous energy consumption and carbon emissions. The main culprit is the ingredient ammonia (NH3), of which we use as much as 230 Mton per year. Although our air consists mainly of molecular nitrogen (N2), plants cannot directly absorb this. Instead, they rely on bacteria (or, in the case of artificial fertiliser, humans) to perform so-called nitrogen fixation, breaking the strong triple bond of molecular nitrogen and converting this into ammonia. Microorganisms can convert this into further nitrogen-containing compounds that the root system can absorb.

Pretty much all of the world’s ammonia production facilities follow the so-called Haber-Bosch process, where hydrogen gas (H2) and nitrogen gas (N2) react together to form ammonia. This method has the benefit that it can be implemented in large, high-yield production lines but comes with the disadvantage of its staggering energy consumption. The inefficiency stems from two essential steps: first, producing sufficiently pure hydrogen and nitrogen gasses, and later, separating the H2 and N2 molecules into individual atoms. Breaking N2 is especially challenging due to its strong triple bond. As an effect, factories operate at extreme conditions, with high temperatures (~400 degrees Celsius) and high pressure (over 200 atmospheres), driven mainly by natural gas. As much as 1.8% of the world’s CO2 emission is caused by factories performing such reactions, consuming around 3-5% of the world’s natural gas production!

Can’t this be done more efficiently? We strongly suspect so. Certain bacteria are also capable of making ammonia, but in a seemingly more efficient way, without high temperatures or high pressure. It would be extremely valuable to copy this trick.

To imitate bacteria, we need to better understand a particular substance, the FeMo cofactor (short: FeMoco), which acts as a catalytic active site during ammonia production. A perfect simulation of FeMoco is not possible on classical computers, as the structure of roughly 120 strongly reacting electrons rapidly becomes intractable. In 2016, researchers from ETH Zurich and Microsoft were the first to report that a moderately large quantum computer could come to the rescue. A few years later, Google researchers refined the prospects even further, describing how simulations could be accomplished with about 4 million qubits and 4 days of computing time.

With FeMoco, we seem to finally have an example that confidently ticks all the boxes for quantum utility: classical methods are limited, we have well-understood quantum methods, and computational outputs have a significant commercial and societal impact. Unfortunately, there is yet another catch - innovation never comes so easily. A recent article17 quotes that industrial production of a ton of Ammonia costs around 26 GJ of energy, compared to at least 24 GJ (estimated) in bacteria. This is indeed not the massive reduction we were hoping for. The article concludes that perhaps the true value lies in a better understanding of this process:

‘The chemical motivation to study nitrogenase is thus less to produce an energy-efficient replacement of the Haber-Bosch process but rather because it is an interesting system in its own right, and perhaps it may motivate how to understand and design other catalysts that can activate and break the nitrogen-nitrogen triple-triple bond under ambient conditions.’

As a final note, we want to stress that quantum computers do not magically spit out recipes for fertilisers, nor for medicines, batteries, or catalysts. For real breakthroughs, we need collaborations between chemists, engineers, and many other experts who spend several years running experiments, having discussions, employing computer simulations, making mistakes, going back to the drawing board a few times, and slowly converging to practical solutions. We should not forget that quantum computers merely provide a new set of tools. The best we can hope for is that smart people will use them in the right way!

Further reading

(Scientific overview article) Prospects of quantum computing for molecular sciences https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s41313-021-00039-z

(Scientific overview article) Quantum Chemistry in the Age of Quantum Computing https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00803

(Scientific article) Toward the first quantum simulation with quantum speedup https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1801723115

Feynman, R.P. (1982) ‘Simulating physics with computers’, International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 21(6), pp. 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02650179. ↩

Lee, S. et al. (2023) ‘Evaluating the evidence for exponential quantum advantage in ground-state quantum chemistry’, Nature Communications, 14(1), p. 1952. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37587-6. ↩

Santagati, R. et al. (2024) ‘Drug design on quantum computers’, Nature Physics, 20(4), pp. 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02411-5. ↩

Hariharan, S., Kinge, S. and Visscher, L. (2024) ‘Modelling Heterogeneous Catalysis using Quantum Computers: An academic and industry perspective’. ChemRxiv. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-d2l1k-v2. ↩

Daley, A.J. et al. (2022) ‘Practical quantum advantage in quantum simulation’, Nature, 607(7920), pp. 667–676. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04940-6. ↩

Chan, G.K.-L. (2024) ‘Quantum chemistry, classical heuristics, and quantum advantage’. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.11235. ↩

Leijnse, K. (2024) ‘Photocatalysis for Water Splitting’, Quantum Application Lab, 8 January. https://quantumapplicationlab.com/2024/01/08/photocatalysis-for-water-splitting/ (Accessed: 28 August 2024). ↩

von Burg, V. et al. (2021) ‘Quantum computing enhanced computational catalysis’, Physical Review Research, 3(3), p.

Hutchins, Mark. ‘Quantum Physics, Supercomputers, and Solar Cell Efficiency’. pv magazine International, 4 August 2023. https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/08/04/quantum-physics-supercomputers-and-solar-cell-efficiency/. ↩

Choi, Charles Q. ‘How Quantum Computers Can Make Batteries Better’. IEEE Spectrum. Accessed 28 August 2024. https://spectrum.ieee.org/lithium-air-battery-quantum-computing.ss ↩

Santagati, R. et al. (2024) ‘Drug design on quantum computers’, Nature Physics, 20(4), pp. 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02411-5. Quote from this article: ‘Current classical quantum-chemistry algorithms fail to describe quantum systems accurately and efficiently enough to be of practical use for drug design.’ ↩

An interesting subtlety is how we measure the energy that the VQE is supposed to optimise. Luckily, there exist very short circuits that we can append to measure the output states in different bases. By running the VQE a relatively small number of times, we can make good estimates of the energy of its output states. This avoids performing the more complex QPE during the optimisation phase. We only need the QPE to produce an accurate representation of the state we’re searching for. ↩

Yung, M.-H. et al. (2014) ‘Introduction to Quantum Algorithms for Physics and Chemistry’, in Quantum Information and Computation for Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 67–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118742631.ch03. ↩

Bauer, B. et al. (2020) ‘Quantum Algorithms for Quantum Chemistry and Quantum Materials Science’, Chemical Reviews, 120(22), pp. 12685–12717. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00829. ↩

Cooper, Peter, Philipp Ernst, Dieter Kiewell, and Dickon Pinner. ‘Quantum Computing Just Might Save the Planet’. McKinsey, 19 May 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/quantum-computing-just-might-save-the-planet. ↩

How and when do we need to act on climate change? (no date) Imperial College London. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/grantham/publications/climate-change-faqs/how-and-when-do-we-need-to-act-on-climate-change-/ (Accessed: 23 September 2024). ↩

Chan, G.K.-L. (2024) ‘Quantum chemistry, classical heuristics, and quantum advantage’. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.11235. ↩