What steps should your organisation take?

Reading time: 12 minutes

Contents

In the previous chapters, we discussed the use cases, the threats, and the timelines of quantum technologies. We will now look at the strategic perspective of a typical non-quantum enterprise. We will assume a typical large-scale organisation that does not sell IT products per se, but relies heavily on computing infrastructure to optimise its operations, supervise processes, communicate with suppliers and clients, and potentially invest in computer-aided R&D. While these organisations may be excited about the potential of quantum computing, they may also feel vulnerable—whether due to competitors advancing ahead or due to hackers attacking legacy cryptography.

The first steps, like growing expertise, finding adequate staff, and doing first proof-of-concept studies, will be largely sector-independent. Further steps can become more organisation-specific, and we will highlight several tools for tailored assessment.

For more bespoke advice beyond this chapter, organisations would typically resort to specialised consultancies. The larger players have extensive writings, for example:

Capgemini – Quantum technologies: How to prepare your organisation for a quantum advantage now

McKinsey – Quantum computing use cases are getting real—what you need to know

We find most of these sources somewhat hyped, emphasising the risks of missing out and urging organisations to start whichever quantum project as soon as possible. Nevertheless, practically all sources (whether academic, governmental or consultancies) agree on the first strategic steps that one should take. We break these down into three stages below.

Common first steps

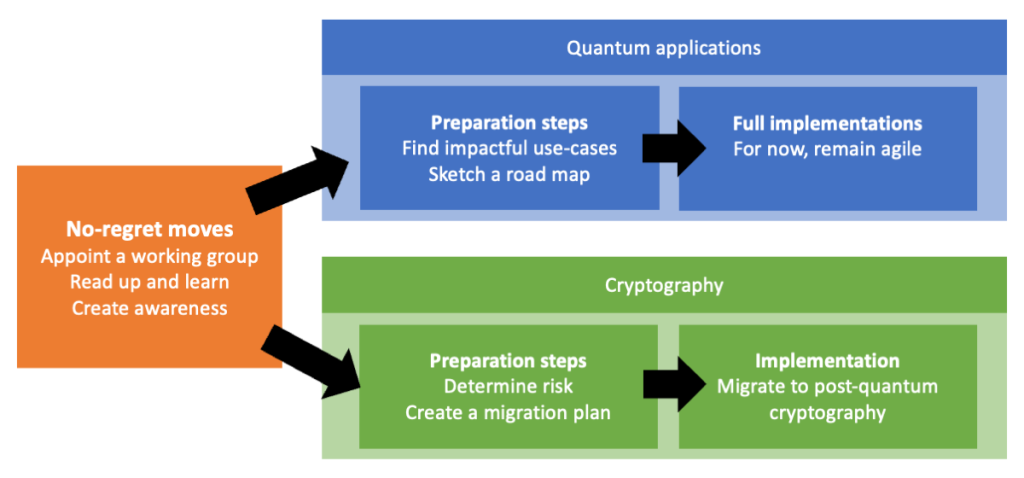

Step 1: Start with no-regret moves

Most companies start with early steps aimed at better understanding the situation. These can be done with very little financial risk.

Some must-do actions:

Appoint a quantum lead or a quantum working group tasked with following the developments.

Read up and learn. If you’ve come this far in this Guide, you’re already doing a fantastic job. We have a separate chapter on further learning resources.

Create internal awareness. Many employees will enjoy inspirational talks, tours or demonstrations that academics or quantum manufacturers can provide.

Optionally:

Put quantum on the agenda with senior management.

Involve collaborators, suppliers and vendors, and make your interest in quantum known. It is to your benefit if suppliers are well-prepared.

Participate in a workshop, hackathon, or similar event.

Towards more concrete actions, it makes sense to split your quantum journey into two different categories:

a. Preparing for quantum applications, where the goal is to leverage quantum technologies to gain some competitive advantage (for example, by strengthening your R&D, further optimising your logistics, improving a product, etc).

b. Migrating to quantum-safe cryptography, where the goal is to keep your IT secure against attackers with a quantum computer.

These endeavours serve very different purposes and are likely spearheaded by different departments. Hence, it seems logical to break these down into separate projects. We discuss further steps in both directions separately.

Prepare to use quantum applications

Step 2a: Explore use cases

At this stage, most organisations will want to make low-regret moves that get them prepared to leverage quantum technologies fairly soon after practical utility becomes available. Some of the bottlenecks could be the lack of in-house knowledge, a limited available workforce, or a long timeline to integrate quantum applications in production environments.

Must do:

Identify the most impactful use cases in your sector.

Sketch a road map for the coming years.

Optionally:

Start concrete proof-of-concept projects. Right now, these are unlikely to offer practical utility and will likely tackle just a toy problem. However, these help build experience in setting up quantum projects and can uncover ‘unknown unknowns’. For staff with a strong physics or mathematics background, it is relatively accessible (and fun!) to get acquainted with quantum programming packages and implement a first test algorithm.

Find strategic partners. Organisations can save costs by collaborating on early, pre-competitive exploration.

Create PR! We notice that many companies are very actively promoting their early results on quantum applications, even if these do not offer significant advantages yet.

Hire staff with a strong background in quantum technologies who understand the market, have the right skills to lead proof-of-concept studies, and can offer advice for strategic decisions.

Step 3a: Implementing actual applications, whenever ready

From here onwards, it gets increasingly difficult to give concrete advice, as priorities may depend on your business and on the way the field of quantum computing will progress. Several sources will simply tell you do ‘develop a long-term strategy’ or similar. Others highlight the need to ‘remain agile’ to quickly adapt to this rapidly evolving field.

For inspiration or a dot on the horizon, you may think towards a competence centre for quantum computing, similar to how many companies have special departments for data science and/or AI. A concrete task could be to elaborate on the list of impactful use cases from the previous step, benchmarking the performance of various quantum and classical software tools. Another task could be to professionalise an earlier proof-of-concept project, bringing it closer to implementation in a production environment.

Identifying fruitful use cases

From a top-down perspective, it is a good exercise to identify your current needs in high-performance computing. What do you currently spend your computing budget on? Are there any areas where new tools in computation or modelling could provide serious business value (for example, by being faster, tackling bigger problems, or delivering higher accuracy)? Which quantities would you ideally have calculated but are beyond the reach of current computers? This results in a longlist of use cases where new computational tools are worth further investigation. The next step would be to research to what extent a quantum computer (or whichever other new computational tool) offers any advantage.

We recommend this top-down approach because it can lead to conclusions sooner, especially because it will identify use cases that are not worth your time (for example, because additional computational power provides little value).

It is also possible to take a bottom-up approach. Looking at the available quantum algorithms, which would speed up processes in your existing IT? Would any of them provide value for your business? This more technical perspective requires some in-depth quantum expertise but can definitely be worth the effort, especially if you have people with the right skills available.

The Quantum Application Lab is a collaboration between various Dutch research organisations. They invite end-users to explore the benefits of quantum computers in projects that last anywhere between 3 and 12 months, ranging between a first exploration of use cases to advanced development of quantum prototype software. Several example projects can be found on their website: www.quantumapplicationlab.com.

Further reading

Scientists propose a framework to discover which real-world problems are potentially accelerated by quantum computers.

Consultant Olivier Ezratti proposes a framework to assess the maturity of quantum computing case studies.

(Youtube) A recording of Quantum.Amsterdam’s online seminar ‘What do companies get out of quantum projects today?‘

What does an R&D collaboration with academia look like?

Several end-users have started collaborations with universities to better understand the use cases of quantum computing. This is often a win-win situation, as companies can learn from renowned experts at relatively low costs, whereas academics benefit from additional funding and showcasing that their research has practical interests. Moreover, many countries provide subsidies for so-called ‘public-private partnerships’. Below, I will sketch my personal experience with the process of starting a public-private partnership.

You will most likely be dealing with a university’s tech transfer office (TTO), which specialises in making in-house knowledge available externally. As a first step, it is important to agree on the scope of the project: what are the research questions, what are the expected outcomes, how long will the project run, and so forth. Ideally, this would be a discussion between an expert from your organisation and a university’s (assistant) professor. The professor will most likely take a supervising role, as the actual work is often executed by a junior researcher employed as a PhD candidate or a postdoctoral (PD) researcher. PhD programs take relatively long, 3-5 years depending on your locale, and it may take some time before the first results come in. Postdoc projects often take 1-3 years and can lead to results sooner, but as of 2024, it can be much harder to hire a postdoc with the right competencies.

When the topic and duration of the project are clear, it is important to discuss details around intellectual property (IP), often done by legal experts. For universities, it is important that researchers can keep building upon the project’s IP in an academic setting. Moreover, they will demand that the results can be published in scientific journals. At the same time, a paying company will want sufficient options to patent new discoveries and will require exclusive use of the IP within their sector. These demands do not necessarily conflict with each other, and in principle, it should be possible to find an arrangement that satisfies both parties.

A straightforward way to ensure that the company learns from the academic developments is by organising meetings or workshops throughout the collaboration project, in which the ongoing R&D is discussed with company staff. The occasional dialogue with company staff is arguably more important than a shiny final report or paper, which risks disappearing in someone’s drawer.

Migrating to post-quantum cryptography

This section relies on technical knowledge from the previous chapter on cybersecurity.

Step 2b: Prepare your migration

Cryptography is a completely different beast, with a more concrete goal, and more urgent timelines for most organisations. Contrary to the applications in the previous section, the cryptography migration is not optional. Luckily, most organisations face the same problem, and there is ample research on effective steps. The core challenge is to upgrade all existing public key cryptography to Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) in the next decade, which could be spread over hundreds or thousands of different applications. Many businesses, especially those dealing with critical infrastructure, may additionally deal with regulators who may or may not have guidelines ready. Moreover, IT transitions can be incredibly slow - it is not uncommon to see plans that cover 5 or even 10 years1.

Authorities seem to agree that the following initial steps should be taken urgently by all large organisations.

Create awareness: make sure that the quantum threat is well-understood in your security departments and among IT managers and product owners throughout the organisation.

Create an inventory of cryptographic assets used within the organisation. This should include both software and hardware and should clearly specify the used algorithms, whether developed in-house or purchased from a vendor. Some parties refer to a ‘cryptographic bill of materials’ (CBOM).

Determine the risk and urgency of PQC migration. Most organisations already perform regular risk assessments of their IT infrastructure. Additionally, organisations should assess whether they classify as an urgent adopter of PQC (see below).

Create a migration plan. This is a more complex step, which should at least prioritise which assets must be migrated first and indicate whether the migration of all urgent systems can be realistically achieved in time, before the arrival of cryptographically relevant quantum computers.

For more details, we recommend following the PQC Migration Handbook, a free guide written by the Dutch secret service AIVD and research organisations CWI and TNO. Security authorities in other countries have made similar guidance available.

Are you an urgent adopter?

Planning ahead to transition to new cryptography can be more critical depending on the organisation. We can distinguish between regular and urgent adopters. You are an urgent adopter when you:

Handle sensitive or personal data with a long confidentiality span.

Handle critical infrastructure on which large groups of people rely.

Provide systems with a long lifespan; hence, your products will still be around when quantum computers are available.

Based on these criteria, a significant fraction of organisations would classify as urgent adopters, such as banks, governments, car manufacturers, grid operators, hospitals, and so forth. Examples of non-urgent adopters could be schools, webshops, travel agencies, some construction agencies, and so forth. Urgent adopters are encouraged to start their migration as soon as possible if they haven’t already.

Step 3b: Migrate

This is a much more technical step for which you will need a well-prepared migration plan from the previous step.

Organisations are strongly discouraged from implementing their own cryptographic functions. The best practice is to rely on standard libraries written by cryptographic experts, which should be safe against a broad spectrum of attacks and have seen careful reviews. We expect NIST’s standards to soon be available in popular open-source packages like OpenSSL or BouncyCastle. This makes the migration less technical, although organisations still deal with the operational challenge of updating a huge number of applications within a limited time.

Due to harvest now, decrypt later attacks, most organisations will focus on updating key exchange algorithms before updating digital signature methods.

On the technical side, cryptographic experts recommend the use of hybrid algorithms that combine the strengths of PQC (to defend against quantum attacks) with a proven conventional public key algorithm (which guarantees at least the original security in case the new PQC algorithm turns out to be less safe than expected). For example, early versions of quantum-safe connections with the Chrome web browser use a combination of X25519 and Kyber-768 (ML-KEM).

Moreover, the practice of cryptographic agility is strongly encouraged, meaning that security protocols can be easily updated and replaced. This is a vague term that isn’t just a software feature - it requires alignment with business protocols and internal policies.

Further reading

To learn more about transitioning to quantum-safe cryptography, we strongly recommend the PQC Migration Handbook written by the Dutch secret service AIVD and research organisations TNO and CWI.

An extension to the handbook is the PQChoiceAssistant, a tool that recommends what cryptographic algorithms are best used in specific situations.

In 2022, the NSA published requirements for national security systems. They indicate a timeline with concrete deadlines between 2025 and 2033.

To illustrate, the PQC Migration Handbook mentions that ‘Judging from previous migrations this process might take well over five years’. The NSA’s requirements for national security systems, published in 2022, demand that quantum-safe algorithms be exclusively used from 2033 onwards. ↩