Quantum hardware

Reading time: 7 minutes

Contents

Conventional computer hardware is extremely reliable. Professional servers are supposed to run non-stop for years without any hardware failures. If you take a new product out of a box, you can be reasonably sure that it will work precisely as advertised - and even if not, it should be straightforward to replace. Moreover, classical IT is extremely well-standardised. No matter what supplier you buy a computer from, you can be reasonably sure you can run your favourite applications on them. Thanks to such high reliability and clear compatibility, it is rather easy to compare different machines, for example, by looking at speed (e.g. floating-point operations per second, FLOPS) and memory size.

We will see that this is radically different for quantum computers. Devices make mistakes, have limited functionalities, and memory is scarce compared to classical computing standards. Several manufacturers focus on niche applications, making trade-offs in certain features to enhance performance in others. In this chapter, we take a high-level perspective at quantum computing hardware. We address the two most important aspects:

What functionality does a device have?

What type of qubits are used?

Different functionalities

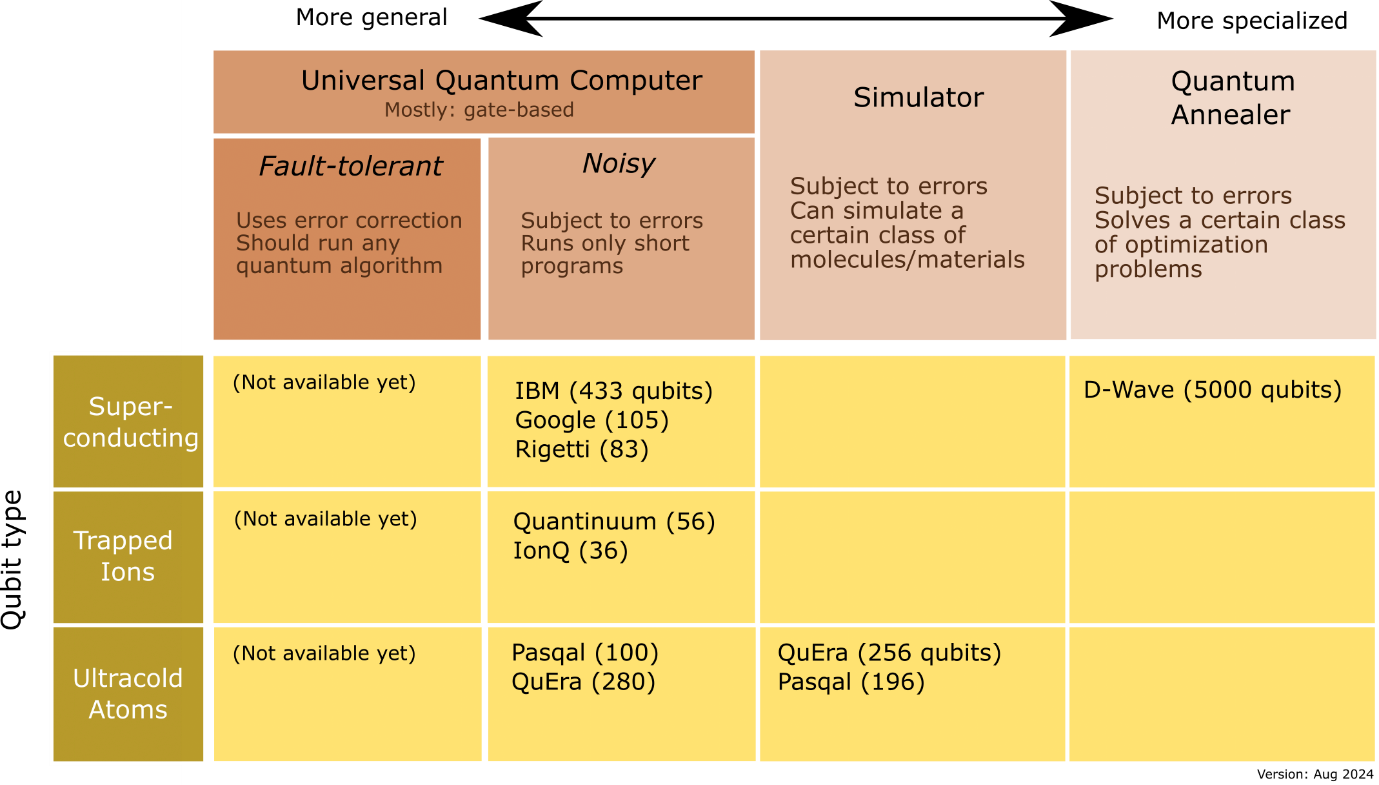

The figure below shows three different functionalities that quantum computers can have (top, red), along with some examples of products on the market (yellow), built from different building blocks. This list is by no means complete! It should, at best, give an indication of the current state of the art. Let us start by taking a closer look at the functionalities.

Our biggest dream is to have a ‘universal quantum computer’. The word ‘universal’ indicates that it can execute any quantum algorithm (or, technically, it can approximate any algorithm’s output to arbitrary precision). For comparison, your laptop, phone, and even a modern coffee machine are universal classical computers, making them capable of running any classical application you can think of: spreadsheets, 3D games, data encryption, and so on. Similarly, a proper universal quantum computer is suitable for any quantum application, regardless of whether it is already known today or invented in the future.

The definition of ‘universal’ is blind to some details, such as memory limitations (it assumes you will never run out of RAM), and omits tedious details about software compatibility (a PlayStation game won’t run on an Xbox). In our high-level overview, such details are unimportant: the main point is that there also exist devices that can not run just any algorithm.

Does a universal computer need to be ‘gate-based’?

No, there are various computational models that are universal.

There are different ways to make a ‘universal quantum computer’. The most popular way is to use a gate-based approach, where elementary operations (‘gates’) change the data stored one or two qubits at a time. This perspective is most intuitive for those used to conventional logical circuits (with AND, OR and NOT gates), and most quantum algorithms are presented in this language. Other alternatives include adiabatic computation and measurement-based computation, which can theoretically run any algorithm written for a gate-based computer without issues and vice versa.

At this moment, gate-based computers are by far the most widespread and appear to be the most popular approach in the race towards a million-qubit quantum computer: nearly all large tech companies rely on this architecture. There is one important exception. Some photonics startups are working towards measurement-based computing, as this overcomes the challenges in performing ‘entangling’ quantum gates with photons. In the following, we will focus mostly on gate-based computers.

No matter what architecture or qubit type you pick, today’s technology will only allow you to run relatively short computations. This is due to the inherent imperfections in qubit construction and control methods. The imperfections cause errors to accumulate, so after some number of steps, the result is almost surely corrupted and unusable. For longer computations, fixing errors on the fly is essential, using so-called error correction.

At the time of writing, we live in the so-called NISQ era, with Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum devices. Many are theoretically fully universal, except that they are limited both in the number of qubits and, most of all, in the number of steps they can execute. Companies like IBM, IonQ, Quantinuum, and Pasqal all have NISQ computers available to test over the cloud.

A universal computer is a jack-of-all-trades, but it excels at nothing. Engineers can make special-purpose devices that improve in certain areas (like the number of qubits or clock speed) by omitting certain functionalities. A quantum simulator specialises in mimicking the behaviour of a particular class of materials or molecules. The precise capabilities can be described in the mathematical language of a ‘Hamiltonian’ that specifies which materials qualify. For example, Harvard-spinoff QuEra offers a quantum simulator over the cloud that mimics a quantum Ising model1. Today’s simulators (like QuEra’s) are fairly similar to a universal NISQ computer, missing only a few essential ingredients, and similarly having restrictions due to noise. Although they look similar, they are not designed to run conventional (gate-based) algorithms.

The jargon around simulators can be a bit confusing. Firstly, the term ‘quantum simulation’ is also used when a classical computer tries to calculate the output of a quantum algorithm. To differentiate, some prefer the term ‘emulation’ for such classical approaches. Secondly, we often hear a distinction between ‘analog’ and ‘digital’ simulation. Ironically, both approaches tend to discretise information over discrete qubits (which I’d call digital). In practice, the terms are rather used to distinguish between continuous and discrete time steps. An analog simulation would use longer, continuous operations on the qubits, whereas a digital simulation uses quantum gates that act in short, discrete bursts on the qubits.

Another special-purpose device is the quantum annealer, popularised mainly by the Canadian scale-up D-Wave. These special-purpose devices can solve a specific class of optimisation problems that goes by the name of QUBO: quadratic unconstrained binary optimisation. There is a well-developed theory of mapping various industrial problems into the QUBO formalism, making annealers fairly versatile machines. However, quantum annealers will never be able to take advantage of the various other quantum algorithms out there: even with enough qubits, we won’t see them cracking codes using Shor’s algorithm.

Further reading

Scale-up Pasqal reports on a material science simulation with 196 qubits and sells a 100-qubit simulator in a EuroHPC tender. In another article, they explain why an ‘analog’ quantum simulation has its advantages.

QuEra makes a 256 qubit simulator available over the Cloud.

Different building blocks

Another important question concerns the materials used to create qubits. Scientists have cooked up several competing approaches, such as superconducting materials, photons, individual atoms, or ions, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. When comparing different qubits, we use the terminology of qubit implementation, the qubit type, or (what we prefer) qubit platform.

The conventional computer electronics industry has settled on a single choice of material and manufacturing process: essentially, all computer chips are made using lithography on silicon wafers. On the contrary, there is an ongoing race between wildly different qubit platforms, and it is still unclear which will eventually be the winner — or whether we will converge to a single winner at all.

There is fascinating physics behind the different hardware types, but we won’t delve into that in this non-technical book (would you otherwise care what material your classical CPU is made of?). However, as soon as you want to test a prototype quantum program on real-world NISQ hardware, you probably want to learn more details. Interested readers are invited to take a look at the references below.

It is interesting to note that all these different functionalities (universal computers, annealers, and simulators) can, in principle, be built using any type of qubit. Returning to the figure at the top, you can see that specific qubit platforms have been used for multiple purposes, and it’s not unlikely that the empty fields will also be populated in the future.

Further reading

Hamiltonian simulation on QuEra’s 256-qubit Aquila machine. https://www.quera.com/events/hamiltonian-simulation-on-queras-256-qubit-aquila-machine (Accessed: 10 September 2024). ↩